Kenya’s growing economy translates into an expanding middle class, thus, increasing demand for housing. According to the National Housing Corporation (NHC), the housing deficit stands at 2.0 mn and has been growing annually by approximately 200,000 units. As such the government introduced ‘provision of affordable housing’ in 2017 as one of its four key pillars for the following five years with the aim of delivering 500,000 units to alleviate the housing crisis. However, three years later, the government has only delivered approximately 228 housing units, an indicator that the target units might just be a pipe dream. The slow momentum is largely attributable to unavailability of financing for both developers and buyers alike. In our previous topicals, we have looked into government strides aimed at resolving the deficit: the establishment of Kenya Mortgage Refinancing Company, Home Ownership Savings Plan and the National Housing Development Fund, among others. Despite the progress made, unavailability of funding continues to be a key impediment to the fruition of the government’s Big Four Agenda on the provision of affordable housing. Therefore, this week, we focus on ways of accelerating funding for affordable housing where we shall cover:

- Introduction to the Current Housing Situation in Kenya,

- Government’s Initiatives Towards the Affordable Housing Initiative,

- Challenges Hindering the Achievement of Affordable Housing,

- Case Study: Singapore, and,

- Recommendation and Conclusion

- Introduction to the Current Housing Situation in Kenya

Kenya’s economy has grown tremendously over the past decade evidenced by the relatively high GDP per Capita of Kshs 198,078 as at 2019, with a ten-year CAGR of 10.1%, according to Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, resulting in the World Bank’s declaration of Kenya as a middle- income country in 2014. The growing economy translates into an expanding middle class, thus, increasing demand for goods and services, including decent housing. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, the Kenyan middle class can be defined as anyone having a disposable income of between Kshs. 23,670 and Kshs. 199,999 per month. However, 74.5% of the working population earns a median gross income of Kshs 50,000 per month or below.

With the increase in economic growth, demand for appropriate housing comes to the forefront. However, in most areas countrywide and for the majority of urban dwellers, access to decent affordable housing has been and remains a pipe dream. Despite the acknowledged importance of housing in Kenya, the demand still outstrips supply. This manifests itself through the increased informal settlements in urban areas with World Bank estimating that 56.0% of the Kenyan urban population live in slums and poor quality housing in rural areas. Delivery of housing to the low to middle-income citizens is further aggravated by inequality and imbalance in housing supply among income groups. Currently, more than 80.0% of new houses produced are for high and upper-middle-income earners, driven by the ease of exit by developers as well as high construction costs, ultimately leaving the low-end and lower mid-end income brackets, who make up approximately 75.4% of the population not catered for.

- Government’s Initiatives Towards the Affordable Housing Initiative

To alleviate the housing issue, the government has made tremendous progress by implementing various policies and fiscal reforms for the past three decades with the aim of enhancing house ownership. So far, the incentives and tax exemptions aimed at driving homeownership in Kenya include:

For Home Buyers:

- Tax exemption on funds deposited under a registered Home Ownership Savings Plan (HOSP) subject to a maximum of Kshs 8,000 per month or Kshs 96,000 per annum, for 10 years,

- Affordable housing relief of 15.0% of gross emoluments up to Kshs 108,000 per annum or Kshs 9,000 per month for Kenyans buying houses under the Affordable Housing Scheme,

- Tax exemption for interest on mortgage repayments up to Kshs 25,000 per month or Kshs 300,000 per annum provided that the taxpayer occupies the property,

- Formation of the National Housing Development Fund (NHDF)- The Fund aims to bridge the gap for affordable housing in Kenya by; enabling end-buyer uptake by providing affordable financing solutions such as the anticipated nationwide Tenant Purchase Scheme (TPS), allowing mortgage and cash buyers to save towards the purchase of an affordable home through the Home Ownership Savings Plan and extending mortgage loans to members at an interest rate of up to 7.0% p.a.,

- Establishment of the Kenya Mortgage Refinancing Company (KMRC) - The facility’s main objective is to grow Kenya’s mortgage market by providing long-term funding to primary mortgage lenders. The facility is set to lend money to local financial institutions at an annual interest rate of 5.0%, enabling them to write home loans at 7.0%, 6.0% points lower than the market rate of approximately 13.0%, and,

- A waiver on stamp duty for first- time home buyers under the affordable housing programme.

- Allowing the use of 40.0% of accumulated pension benefits for the purchase of a residential house in addition to the previous use of 60.0% as mortgage collateral.

For Developers;

- Reduction in corporate tax by 50.0% from 30.0% to 15.0% for developers of over 100 affordable housing units annually,

- Exemption from Value Added Tax for supplies imported or purchased for direct and exclusive use in the construction of affordable houses by licensed Special Economic Zones (SEZ), subject to; i) recommendation of the Cabinet Secretary for Housing, and ii) a minimum of 5,000 units to qualify,

- A 25.0% tax exemption for investors in commercial property, who spend on social infrastructure such as power, water, sewer lines, and roads to allow recovery of their expenses within 4-years, and,

- The waiving of building approval fees for all affordable housing projects in Nairobi, under the Nairobi City County Sessional Paper Number 1 of 2018.

- Challenges Hindering the Achievement of the Affordable Housing

Despite the above incentives, Kenya has failed to develop a robust housing finance system leading to relatively low homeownership rates. According to the 2015/16 Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey (KIHBS), only 26.1% of Kenyans living in urban areas own the homes they live in. This is in comparison to countries like South Africa and the United States with 53.5% and 64.5%, respectively. Those who own homes rely mainly on savings and other sources of financing including commercial bank loans, and local investment groups commonly referred to as chamas, and Savings & Credit Co-operative Societies (SACCOs). Mortgage loans uptake remains relatively low totaling to 26,554 as at December 2018 out of an adult population of 23.0 mn. On the supply end, the Kenya residential market has continued to witness increased activities within the high-end markets fueled by the relatively good returns as investors can charge a premium on units within these submarkets. However, the highest demand for housing remains within the low and mid-end markets, which have suffered low supply as developers are not keen on such submarkets, given the relatively low property market prices and resultant low returns.

The main challenges facing housing include;

- Inadequate Supply of Affordable Development Class Land - There is an inadequate supply of serviced land at affordable prices due to soaring land prices in urban areas, which has led to increased development costs as land costs account for 25.0% - 40.0% of development costs in urban areas, which consequently impacts on end-user property prices,

- Costs of Construction - Mid-level construction costs in Kenya range from Kshs 44,000 - Kshs 64,000 per square metre (SQM) depending on the level of finishes, height and other related factors, which account for 50.0% - 70.0% of development costs. Considering a mid-level 2-bed house of 70 SQM, the construction cost alone would be at least Kshs 3.0 mn using a rate of Kshs 44,000 per SQM, meaning the total development cost will range from Kshs 4.0 mn - Kshs 6.0 mn, limiting the affordability of such a house,

- Inadequate Infrastructure - Several parts of Kenya lack the requisite infrastructure for development, such as proper access roads, power and sewerage services. Developers are thus forced to incur these costs, which are then passed on to the end buyer,

- Access to Finance for Development - Real estate development is a capital-intensive investment and thus, developers have to explore alternative sources of capital, which come at a relatively high cost ranging from 14.0% - 18.0% per annum,

- Access to and Affordability of Mortgages - Access to mortgages in Kenya remains low mainly due to; i) low-income levels that cannot service a mortgage, ii) soaring property prices, iii) high interest rates and deposit requirements which lockout many borrowers, iv) exclusion of employees in the informal sector due to insufficient credit risk information, and v) lack of capital markets funding towards real estate purchases for end buyers. According to Central Bank of Kenya, there were only 26,554 mortgage accounts in Kenya as at December 2018 out of a total adult population of approximately 23 mn persons, with the mortgage to GDP ratio standing at 3.1% in 2016 compared to countries such as South Africa and the USA, which have a ratio of above 30.0% and 70.0%, respectively,

- Underdeveloped Capital Markets Infrastructure – Financing for real estate is capital intensive and cannot be done by only bank financing. In more developed economies, businesses depend on banks for only 40.0% of the funding with the balance coming from alternative channels such as capital markets. However, in Kenya businesses rely on banks for over 95.0% of the funding with only 5.0% of funding coming from capital markets. To increase funding from capital markets, we will need to open our capital markets from the current restrictive rules and regulations, which serve to constrain capital markets development. Specifically, we need; (i) expedited and time-bound approval processes, (ii) liberalize eligibility for Trustees beyond the current few banks, who are also conflicted, to include Corporate Trustees, (iii) enable unit trust funds to have as many bank custodians as necessary to serve their clients, (iv) reduce the minimum investment required for development REITs from the current Kshs. 5 million, which is too high given the current median income of just Kshs 50,000 per month, (v) expand room for private offers to increase the diversity of funding available in the market, (vi) allow for specialized collective investment schemes so that investors can invest in funds focused on housing, as current rules only allow up to 25.0% investment into one asset class, and (vii) reduce the capital requirements for a REIT Trustee from Kshs 100 million, which has limited the REIT trustees to less than 3 players,

- Ineffectiveness of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) for Housing Development - The government has previously enlisted the help of the private sector for financing and development of affordable housing. This has however not achieved the intended objective as a result of:

- Regulatory hindrances such as lack of a mechanism to transfer public land to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) to facilitate access to private capital through the use of the land as security,

- Lack of clarity on returns and revenue-sharing,

- The extended time-frame of PPPs while private developers prefer to exit projects within 3-5 years, and,

- Bureaucracy and slow approval processes.

- Case Study: Singapore

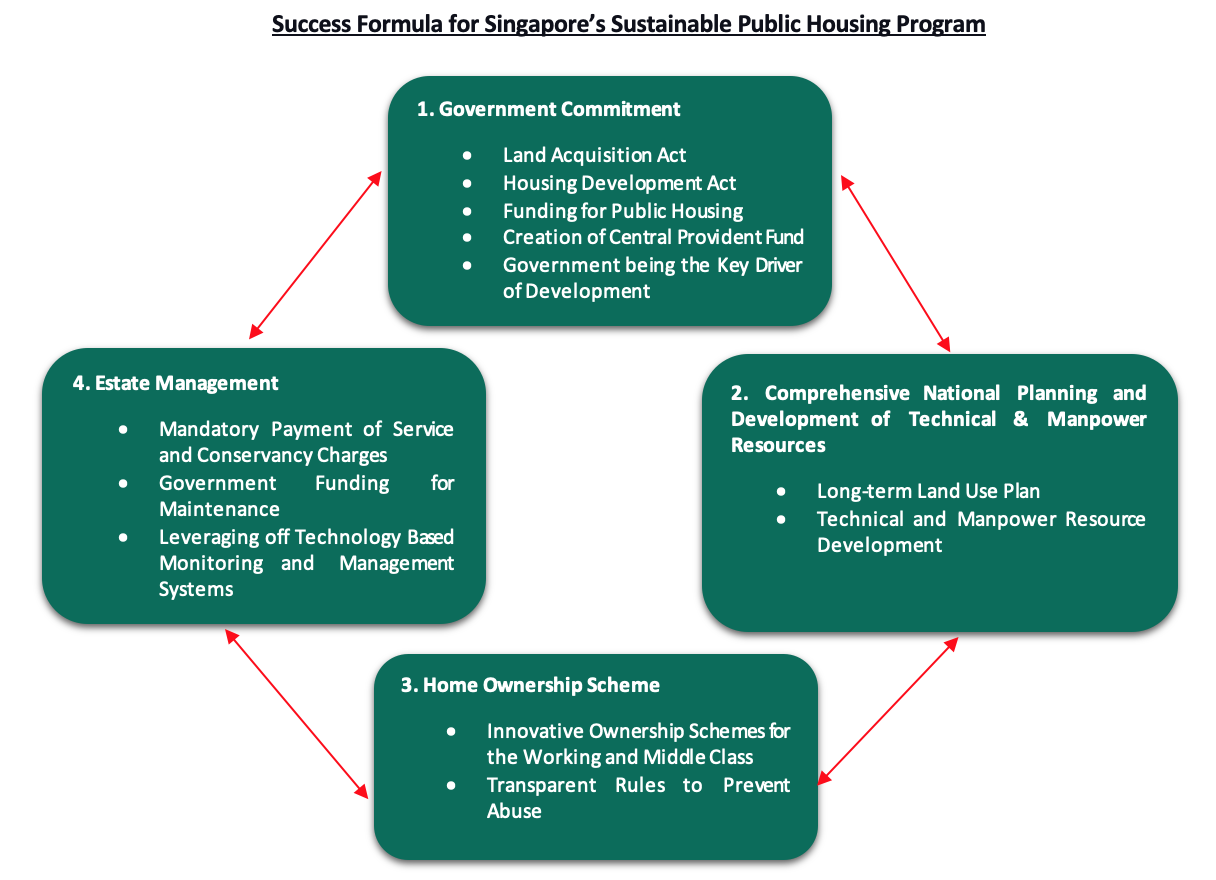

Singapore is a country with one of the best housing solutions in the world. In 1960, just after acquiring independence, Singapore had a cumulative housing requirement of 147,000 units for the 10-year period that ended in 1969 for a population of 1.6 mn people, which was growing at 6.4% per annum. The private sector could only provide approximately 2,500 housing units per year and at price levels out of reach for the low-income segment. The government, therefore, put in place policies and strategies to promote home-ownership for its residents. According to the World Bank, as at 2018, 80.0% of Singaporeans lived in houses built by the government, through the Housing Development Board (HDB) (the equivalent of the National Housing Corporation in Kenya), with 90.0% being owner-occupied, yet when they attained self-government in 1959 only 9.0% lived in public housing.

Some of the initiatives that have led to the fruition and sustenance of affordable housing in Singapore are:

- Establishment of the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) in 1927 by the British colonial government to carry out town planning, slum clearance and to provide low-cost housing for resettled residents and low-income earners, and,

- Establishment of the Housing and Development Board in 1960 by the Singapore Government whose top priority was to ramp up a large-scale public housing program that would be able to house the majority of the population.

NOTE: Central Provident Fund (CPF):- is a compulsory comprehensive savings and pension plan for working Singaporeans and permanent residents primarily to fund their retirement, healthcare, and housing needs in Singapore.

The public housing program in Singapore has been enabled predominantly by the availability of funds from the general government tax revenue and the Central Provident Fund (CPF). Similar to the National Housing Development Fund in Kenya, Singapore has in place the Central Provident Fund which was initially installed as a vehicle for housing finance. A major policy innovation was later implemented to allow withdrawals from the fund to finance the purchase of houses sold by the Housing Development Board. When the CPF was established in 1955, both employers and employees contributed 10.0% (5.0% each by employees and employers) of the individual employee’s monthly salary toward the employee’s personal and portable account in the fund. The contribution rates in 2016 were 20.0% of wages for employees (the portion of pay withheld by an employer to go into the CPF account) and 17.0% of wages for employers (an amount an employer is required to pay into an employees’ CPF account out of their own pocket, above and beyond the stipulated salary), up to a monthly salary ceiling of an equivalent of Kshs 44,000.

The Housing Development Board (HDB) receives government loans to finance its mortgage lending and pays interest at the prevailing CPF savings rate. The HDB uses the loans to provide mortgage loans and mortgage insurance to buyers of its leasehold flats (both new and resale). The typical loan represents 80.0% of the price of the flat. The maximum repayment period is limited to 25 years. In Singapore, every household can apply for a maximum of two HDB loans. The mortgage interest rate charged by the HDB is pegged at 0.1% points above the CPF ordinary account savings interest rate. The latter is based on savings rates offered by the commercial banks, subject to a minimum of 2.5%. The use of CPF savings for the purchase of public housing has been an important factor in making the homeownership program in Singapore possible and successful.

Initially, HDB introduced the homeownership scheme which aimed at providing public housing for people whose housing needs were not met by the private sector. The scheme then grew slowly because of the small number of flats available and the requirement of a handsome amount of down payment. To improve the situation, a CPF Act was introduced to allow members to withdraw up to 80.0% of their total CPF savings to purchase a flat. The Act also stipulated that the employers and employees had to contribute a monthly sum to the employees’ CPF accounts. As the returns on CPF savings are low comparing to the price increase in public ownership flats, most residents chose to withdraw their CPF savings to purchase public flats to maximize the returns of their savings. This mandatory savings deposited with the government had built up a huge capital reserve for the government to finance housing developments and simultaneously enabled all CPF members to purchase their houses and meet their initial and mortgage payments. Therefore, utilization of savings can enhance homeownership by either fully settling the unit sale value or the deposit.

These are the financing options for each type of housing as provided by the Housing Development Board:

- Build to Order: These are apartments that HDB sells off-plan. This is financed by the HDB loan by banks which lend at a fixed rate of 2.6%. Accessibility to this loan requires individuals to pay a very little amount of cash or none provided they have enough CPF savings,

- Design, Build and Sell Scheme:Units built under this scheme were for public housing but were developed by private developers. The scheme was however suspended after 2015 due to the unsatisfactory spaces of units and high prices charged by developers which led to poor reception, and,

- Executive Condominiums:These are more executive apartments built and sold by private developers to buyers who can exceed Housing Development Board income ceilings but cannot afford private homes. Individuals pursuing these developments get bank loans and get to choose a floating rate package.

In conclusion, key take-outs and lessons Kenya could take up from the Singapore housing system would be;

- It will be challenging to deliver affordable housing without a comprehensive urban plan and hence, to meet housing demand sustainably, there is a need to have efficient urban planning measures in place,

- Without adequate incentives, the private sector will not be empowered enough to significantly contribute to the housing supply, and,

- Just like in Singapore, there is a need to consider the use of social security payments as a down payment for housing.

- Recommendation and Conclusion

Accessing funding for real estate continues to be a key challenge in Kenya, and especially with the need to fuel the government’s initiative on the provision of affordable housing with the target of developing approximately 500,000 housing units by 2020. Borrowing lessons from the case study in Singapore, the private sector is also a key player in resolving the housing deficit. Majorly, the private sector’s participation in the development of affordable housing in Kenya has been crippled by the unavailability of financing in the wake of tough economic times, bank dominance where approximately 95.0% of financing is from banks and only 5.0% is obtained from other sources according to World Bank and the relatively high cost of funding in Kenya. Learning from developed countries such as Singapore and the United Kingdom, capital markets play a key role in the mobilization of commercial financing mainly to boost housing. Therefore, while seeking to accelerate funding for affordable housing development, there is a need for consideration of ways of deepening capital markets and access to non-bank funding. Some of the ways of achieving this include:

- Reduced Minimum Amount Investable in Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT) - The hefty minimum investment required for a REIT has continued to push away potential investors. Therefore, to attract capital into capital markets vehicles such as REITs to develop affordable housing, there is a need to conduct a review on the REIT. The current regulations, which define the minimum subscription amount per investor at Kshs 5.0 mn for a Development REIT (D-REIT) is too high to attract significant interest from a diverse set of investors. An amount of approximately Kshs 1.0 mn ensures the investor is sophisticated while also allowing a larger pool of investors to participate,

- Development Of Structured Products In The Kenyan Market – Structured products have been a welcome alternative to banks for businesses seeking capital for growth, and the same can come in handy in the funding of affordable housing projects. Currently, the supply of affordable housing has been significantly crippled by the unavailability of financing with 95.0% of the funding being sourced from banks while only 5.0% from other alternative funding. Thus, the market lacks favorable options which would otherwise be availed through structured products at competitive rates thus increasing the development of affordable housing,

- Review of the Regulations of Pension Schemes Funds to be Invested in a Residential House- According to the Retirement Benefits Regulations, citizens can utilize a proportion up to 40.0% of their accumulated benefits subject to a maximum of 7 million towards the purchase of a house, in addition to using up to 60.0% of the same as mortgage collateral. However, as is the 40.0% may prove to be insufficient for some members, hindering the ambitions of becoming a home-owner, and thus not achieved the intended impact. Therefore, there is need for a review of the same and we propose matching what already exists as an allowable limit for mortgage loans guarantees. Additionally, the members should be allowed to select the developer they would wish to buy the house from,

- Review of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) - There is still uncertainty regarding revenue-sharing and the returns to private investors in PPPs, as well as policies that will curtail corruption and bureaucracy associated with government projects. In addition, private developers are likely to shy away from projects of more than 5 years given the uncertainty associated with transitioning to a new government after the end of the current term. Unless resolved, the above issue is likely to continue resulting in the ineffectiveness of these PPPs,

- General Bureaucracy and Ineffective Policy Actions: To deliver the high numbers of affordable housing units required, the process of land and real estate transactions need to be much faster and less susceptible to rent collection by gatekeepers. Policy actions, such as the reduction of income tax for developers producing 100 affordable units annually from 30.0% to 15.0%, need to be clear and accessible, and,

- Specialized Collective Investment Schemes- To allow for the mobilization of funds specifically for affordable housing projects, there is need for the Capital Markets Regulations to allow for the formation of a Collective Investment Scheme that invests in a single asset class or is formed for a specific purpose or specific sectors such as affordable housing, technology or financial fund etc.

In conclusion, the supply of affordable housing units has mainly been constrained by the unavailability of financing, especially with the current bank dominance. There is, therefore, the need to mobilize alternative sources of funding, particularly the opening up of capital markets’ access to developers, which will provide a low-cost capital raising mechanism, thus, fill in the existing financing gap in addition to complementing the government efforts aimed at driving one of the government’s Big Four Agenda on the provision of affordable housing.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.