Introduction:

Kenya’s public debt continues to be a topic of discussion in most macroeconomic outlook discussions, with global credit rating agencies such as Fitch Rating expecting the pandemic to halt the country’s fiscal consolidation and increase its financing needs. Most recently in December 2019, Fitch affirmed Kenya’s B+ rating owing to the country’s strong and stable growth outlook, however, they cited failure to stabilize government debt to GDP levels could lead to a negative rating action. In the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic, economic effects of the virus continues to increase with the number of cases rising and the number of deaths escalating. As such, risks abound on revenue collection and increased expenditure resulting from capital required to control the pandemic leading to increased fiscal pressure given the existing huge fiscal deficit. It is for this reason that this week, we shall cover debt relief as an option available to the government in mitigating the effects of the pandemic. Therefore, we shall cover the following:

- Kenya’s Current Debt Levels and Debt Profile,

- Impact COVID-19 Has Had on The Economy, With a Focus on Debt Sustainability,

- Kenya’s Debt Servicing Levels and Why It Is Important For Kenya To Seek Debt Relief, and,

- Conclusion and Our View Going Forward.

Below is a summary of what we have written so far on the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Impact of Corona Virus on the Kenyan Economy: We analyzed the resultant effect on the Kenyan economy given the negative impact that the pandemic is having on international trade, the financial and commodity markets, and the global macroeconomic environment;

- The Potential Effects of COVID – 19 on Money Market Funds: Here we highlighted the current macro-economic environment in the country, where we analyzed the effects in the fixed-income market and how things stand, having reported the first infection on 13thMarch 2020; and,

- COVID-19 Economic Containment Policies: Here we highlighted the options available to the Kenyan Government when it comes to managing the adverse economic effects brought about by the pandemic.

Section I: Kenya’s Current Debt Levels and Debt Profile

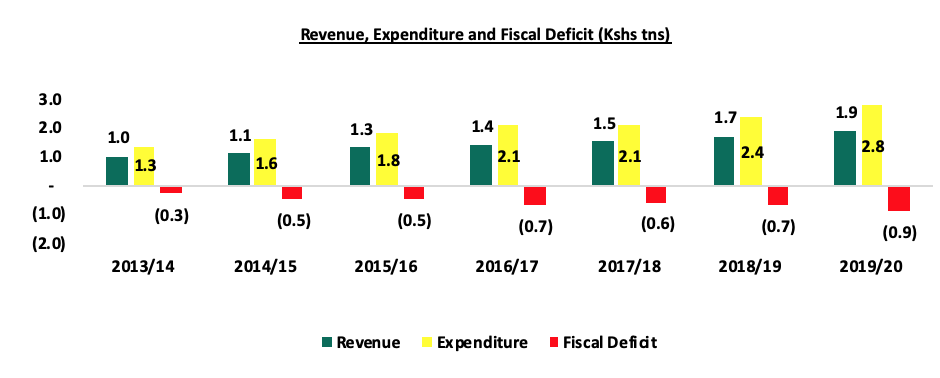

Year on year, the national budget has continued to grow, with total expenditure growing at a 6-year CAGR of 16.6% to an estimated Kshs 2.8 tn in FY’2019/20 according to the 2020 Supplementary II budget estimates, from Kshs 1.3 tn as at the end of FY’2013/14. Revenue growth on the other hand has grown at a slower 6-year CAGR of 13.1% to an estimated Kshs 1.9 tn in FY’2019/20, from Kshs 1.0 tn as at the end of FY’2013/14. The faster rise in expenses, compared to revenue collected has seen the fiscal deficit widening from Kshs 0.3 tn (equivalent to 5.6% of GDP) in FY’2013/14 to a projected Kshs 0.9 tn (equivalent to 8.0% of GDP) in FY’2019/20 as per the 2020 Supplementary II budget estimates as highlighted in the chart below:

Source: National Treasury

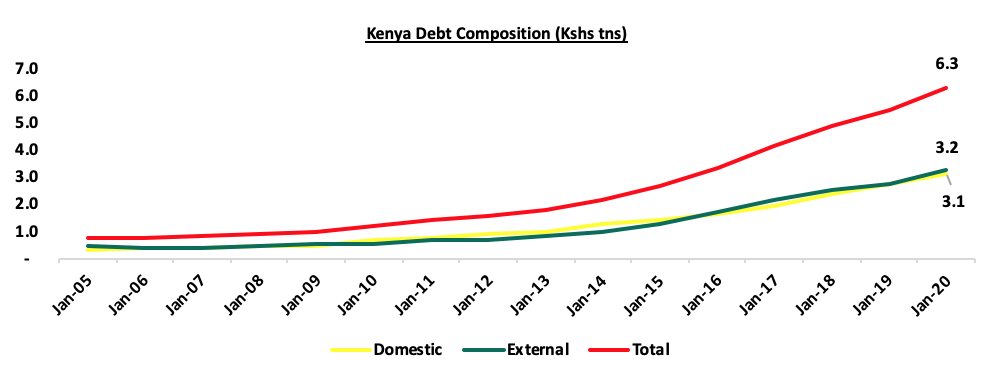

This has necessitated increased borrowing in order to fund the fiscal deficit. Consequently, this has seen the levels of debt increasing, with the debt to GDP ratio rising from 46.0% to an estimated 62.0% during a similar period of review according to the IMF, and above the IMF’s recommended threshold of 50.0%. To further facilitate more borrowing, recently, the Public Finance Management (PFM) Regulations was amended, to substitute the debt ceiling that was previously pegged at 50.0% of GDP to an absolute figure of Kshs 9.0 tn. Given that the country’s total public debt currently stands at Kshs 6.3 tn, ( Kshs 3.2 tn foreign and Kshs 3.1 tn, domestic borrowing), this gives the government a leeway of borrowing an extra Kshs 2.7 tn to reach the Kshs 9.0 tn limit.

The government uses two sources to access debt financing:

- Domestic Markets: This is through issuance of treasury bills and bonds, or can seek to borrow from

- International Markets: This is through multilateral lenders (international institutions such as the World Bank that provide financial assistance in form of loans or grants), bilateral lenders (other nations that provide debt) or through commercial lenders from the international capital markets through the issuance of sovereign bonds/Eurobonds.

The country’s debt mix currently stands at 51:49 external and domestic debt, respectively. In figurative terms, this comprises of Kshs 3.2 tn in external debt and Kshs 3.1 tn in domestic debt. This is in comparison to the 59:41, external and domestic debt structure as at the end of 2005, and against a debt strategy target mix of 60% foreign and 40.0% domestic debt. Kenya’s foreign public debt has also evolved with the exposure to bilateral and multilateral development institutions declining, to a much more commercial funding structure comprising of Eurobonds and syndicated loans. This has seen the proportion of Bilateral and Multilateral debt, which stood at 90.7% of total external debt as at June 2013, declining to approximately 66.4% as at December 2019. This has seen commercial loans, deemed more expensive because of their high interest costs compared to soft loans from bilateral and multilateral development institutions, grow from a low of Kshs 58.9 bn as at June 2013 to Kshs 1.0 tn as at December 2019, equivalent to 33.1% of total foreign debt, with suppliers credit accounting for the remaining 0.5% of the total foreign debt.

Source: National Treasury and CBK

Section II: Impact COVID-19 Has Had on the Economy, With a Focus on Debt Sustainability

Kenya’s economic growth is expected to slow down, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) revising Kenya’s 2020 GDP growth rate for 2020 to 1.0%, from the 6.0% growth rate projected at the beginning of the year in their World Economic Outlook (The Great Lockdown). The World Bank in their Kenya Economic Update have also revised Kenya’s GDP growth rate for 2020 to 1.5% if economic activities are disrupted for 2-months or a recession of (1.0%) if economic activities are disrupted for longer than 3-months. Our in house view also indicates a lower GDP growth rate of 1.4% - 1.8% for the year 2020 depending on the severity of the outbreak and economic implications for Kenya. One of the key elements of debt sustainability in any economy is the ability to service debt, and this is usually measured by revenue collection to total outstanding payments required, both in principal and interest payments. The pandemic has so far had a negative impact on revenue collection and borrowing costs and the situation is expected to worsen as highlighted below:

- Revenue Collection: Revenue collection activities of the government has been affected due to the ongoing pandemic with major economic sectors such as tourism, manufacturing and agriculture feeling the brunt effects of the pandemic following supply side shocks, decline in export demand and reduction of tourism and remittance flows. In addition, revenue collection is also expected to be suppressed following, the president signing the Tax Amendment Bill 2020 into law in effect reducing taxes, both income tax and VAT, in order to cushion individuals from the adverse effects of the pandemic. Over the years, government has heavily relied on taxes in order to raise revenues with both VAT and income tax jointly contributing an estimated 60.8% to the FY’2019/20 total revenues as per the 2020 Supplementary II budget books,

- Expenditure: The government’s expenditure is expected to increase to an estimated Kshs 2.8 tn according to the 2020 Supplementary II budget estimates, from Kshs 2.7 tn in the FY’2019/2020 budget, following additional spending to strengthen the health care system to withstand a potential spike in COVID-19 infections, protect vulnerable households and to ease firms’ liquidity constraints. As a result, the fiscal deficit is expected to rise to 8.0% of GDP in 2020 from a pre-COVID-19 target of 6.3% of GDP therefore increasing pressure for the government to seek additional domestic borrowing in order to plug in the financing gap arising from the COVID-19 fiscal measures. This has already seen the government raising its domestic borrowing to Kshs 404.4 bn from the initial 300.3 bn as per the 2020 Supplementary II budget estimates, and,

- Increased Borrowing Costs: Kenya’s foreign debt is mostly denominated in foreign currency therefore the volatility of the exchange rate plays a key role in determining our borrowing costs. The Kenyan Shilling has been depreciating due to the uncertainty created by Coronavirus with the YTD depreciation against the US Dollar currently at 5.9% as at 30thApril 2020, in comparison to the 0.5% appreciation in 2019. The depreciation of the local currency has made external debt more expensive, with 69.0% being US Dollar denominated, 18.1% in Euro, 5.5% in Chinese Yuan, 4.5% in Japanese Yuan, 2.6% in Great Britain Pound and other currencies account for 0.3%, hence increasing the danger of rising debt-service costs. The expectations of slower revenue collection attributable to slower economic growth as a result of the ongoing pandemic, coupled with higher financing costs is likely to deteriorate the debt servicing capabilities of the country and as such presenting a higher risk of debt distress.

Section III: Kenya’s Debt Servicing Levels and Why It Is Important for Kenya to Seek Debt Relief

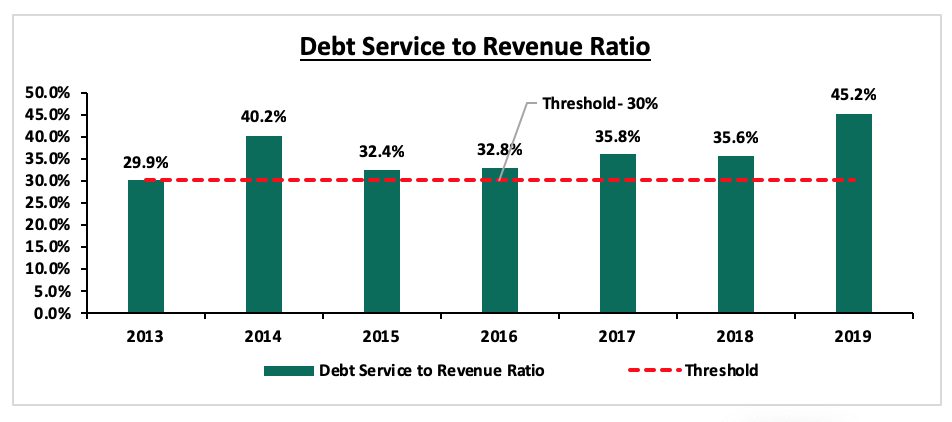

According to the National Treasury, the debt service-to-revenue ratio was estimated at 45.2% as at the end of 2019, higher than the recommended threshold of 30.0% and as such elevating the risks of repayment following shocks arising from the ongoing pandemic and low revenue collection. Below is a chart showing the evolution of the country’s debt service to revenue ratio:

Source: IMF Country Report & National Treasury Annual Public Debt Report

In the FY’2019/2020 budget, Kshs 800.0 bn had been set aside to repay loans of which Kshs 366.4 bn was expected to cover for interest payment with the largest bulk of debt repayment falling to China. As at December 2019, the amount of external debt owed to China (Kshs 693.1 bn) accounted for 67.7% of total bilateral loans, compared to 57.0% in 2016. The amount owed to China is approximately 5 times more than what is owed to the next biggest lending partner Japan, accounting for 13.4% (Kshs 137.2 bn) of the total bilateral loans. Hence, this has resulted in debt concentration risks in China.

Due to the increased debt distress risk, it is important for the Kenyan Government to seek debt relief and our focus on this week’s note is the options available on debt relief as a measure of mitigating this risk. Debt relief refers to the reorganization of debt to provide the indebted party with a measure of respite, either fully or partially. The debt relief can either be through reducing the outstanding principal amount, lowering interest rates on loans due or extending the term of the loans. In the ongoing global pandemic, the IMF executive board approved immediate debt service relief to 25 of the IMF’s member countries, 19 being African countries, under the IMF’s revamped Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT) as part of the Fund’s response to help address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Kenya was not among the 25 countries that received the debt relief facility because of its per capita income, which stood at Kshs 181,260 above the Kshs 128,790 required by IMF to receive the debt facility. Kenya’s debt to the IMF is also relatively small at Kshs 36.5 bn in December 2019, accounting for a meagre 3.5% of the total multilateral debt. The World Bank, in partnership with the IMF and the international community, has over the years worked with developing countries to reduce their debt burdens, through:

- The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative: The program was launched by the World Bank and IMF to ensure that the poorest countries in the world are not overwhelmed by unmanageable or unsustainable debt burdens. This was in response to accumulation of unsustainable and developing country debt by most countries. The program called for voluntary debt relief from all creditors, and gave eligible countries a fresh start on foreign debt that had placed too great a burden on resources for debt service, and,

- The Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative: The debt relief program was launched to help countries that had graduated from HIPC and were struggling to make progress towards the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The program offered full debt relief for eligible debt from the World Bank's International Development Association (IDA), the IMF, the African Development Fund and the Inter-American Development Bank held by low-income countries that have completed the HIPC process.

Given that the debt service to revenue ratios are above the recommended threshold of 30.0% and the devastating effects of the pandemic, coupled with the urgent need to prevent the worsening of debt ratios, which may lead to lower social expenditures and increase poverty. It is imperative that the government seeks temporary debt moratorium or debt forgiveness so as to provide the country some breathing space and offset some of the negative effects of contracting government revenues. It is therefore important that the Kenyan Government should consider seeking debt relief through;

- Temporary Debt Stand Still: According to the 2020 supplementary budget II estimates, Kshs 131.9 bn is expected to cover for interests to external debt and therefore a temporary stand still of debt servicing will be important in providing fiscal space for the country. With a large portion, (67.7%) of Kenya’s bilateral loans being owed to China, approaching the Chinese Government for a temporary stand still of debt servicing will see Kenya save approximately Kshs 84.3 bn in FY’2020/2021, which is targeted towards debt servicing to China as per the 2020 Supplementary budget II budget books.China has a history of working with struggling borrowers in an aim to ease short-term pressure to ensure eventual repayment and in light of G20 states, of which China is part of, agreeing to postpone some of Africa’s debt by a year for Africa’s poorest countries, there already exists a precedence for relief on this front. With the country, having lost market access for our exports and a substantial loss in major revenue sources obtaining a temporary debt standstill will be important for the country. A temporary stand still from China would be the first step towards a broader debt relief, with China’s economy also expected to contract for the first time in three decades, which is a factor that makes a temporary debt stand still a realistic and immediate approach,

- Paris Club Activities: Paris Club is a group of officials from major creditor countries whose role is to find coordinated and sustainable solutions to the payment difficulties experienced by debtor countries. Kenya’s second largest lender, Japan, accounts for 13.4% of the bilateral loans and is a permanent member of the Paris Club, therefore Kenya could approach the Paris Club to restructure the debt owed to Japan. Previously Kenya has gone to Paris Club three times for rescheduling in 1994, 2000 and 2004, managing to reschedule a debt in 2004, amounting to USD 350.0 mn. Kenya has also managed to reschedule debt amounting to Kshs 5.8 bn from Japan to help bridge its budget deficit for the 2000/2001 financial year and if a similar agreement is reached Kenya could save approximately Kshs 5.1 bn in debt servicing to Japan in FY’2020/2021 as per the 2020 Supplementary II budget books,

- Accessing IMF Emergency Financing and Raising IMF Special Drawing Rights: With the IMF Executive Board having approved the proposal to enhance the fund’s emergency financing toolkit to USD 100.0 bn (Kshs 10.7 tn), access to this fund will provide additional liquidity to the country and serve as a bridge special purpose vehicle for commercial debt servicing. The government has already received Kshs 6.0 bn from the World Bank and is in talks to receive Kshs 75.0 bn from the IMF. As at December 2019, Commercial loans accounted for 33.1% of the external debt and therefore emergency financing from the IMF to help service commercial loans will aid in addressing debt distress, and,

- Debt Swap for Sustainable Development: This is where a creditor forgives debt on the condition that the debtor makes available some specified amount of local currency funding to be used for specific developmental purposes. Debt-for-development swaps provide for win- win situations as debtors see their debt reduced and development spending increased, while creditors benefit from an increase in the value of remaining debt claims and increase their development credentials. In 2006, the Governments of Italy and Kenya signed an agreement, the Kenya- Italy Debt- for- Development Programme (KIDDP), to convert bilateral debt owed by the Kenyan Government to the Italian Government into financial resources to implement development projects aimed at poverty reduction. If the Kenyan Government was to seek a debt swap with Italy under the same terms, approximately Kshs 35.7 bn could be saved, which is what the country owed to Italy as at December 2019. On this front, the United Nations together with the World Bank, IMF and other Civil Societies have been driving his agenda in a bid to free up countries from debt payment across a resource-rich Africa.

Section IV: Conclusion and Our View Going Forward

The public debt in the country is a point of concern with both the debt to GDP ratio as well as the debt service to revenue ratio having exceeded the recommended threshold. The trend is worrisome as the economy is likely to face fiscal challenges arising from the global pandemic. This has been echoed by various authoritative bodies, with indications currently pointing to a possible further downgrading of Kenya’s creditworthiness currently at ‘B+’ by the global rating firm Fitch. In comparison to the size of the stimulus packages for developed countries, the total amount received from debt relief is miniscule. However, it could provide an important fiscal breathing space and to offset to certain degree the loss incurred by contracting export revenue and decline in other financial inflows. Factoring the current debt levels and the risks abound in the medium term, we are of the view that in light of the ongoing pandemic and global recession looming, for the government to reduce our debt levels, in line with the IMF sustainable levels, it should consider;

- Negotiating for a temporary debt stand still. Kenya could save approximately Kshs 84.3 bn in debt servicing to China and with precedence already existing on debt stand still, following G-20 nations agreeing to postpone some of Africa’s debt, the stand still would be a realistic and immediate approach,

- Paris Club activities in seeking debt relief to avoid sinking into a debt trap. The government should approach the Paris Club to seek relief from Japan since they are the second largest lenders to the country. Because of the shocks caused by the crisis, MDRI and HIPC Initiative might not be adequate to sustain the impact, therefore the government needs to take a multi-pronged approach to tackling the challenges of developing countries while taking into consideration the challenges posed toward maintaining debt sustainability, in view of the building up of pressure on debt servicing,

- Accessing IMF emergency financing and raise IMF special drawing rights to provide additional liquidity and serve as a bridge special purpose vehicle for commercial debt servicing, and,

- Debt swap for sustainable development since they offer a win-win situation through reduction of debt and development spending increased, while creditors benefit from an increase in the value of remaining debt claims.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.