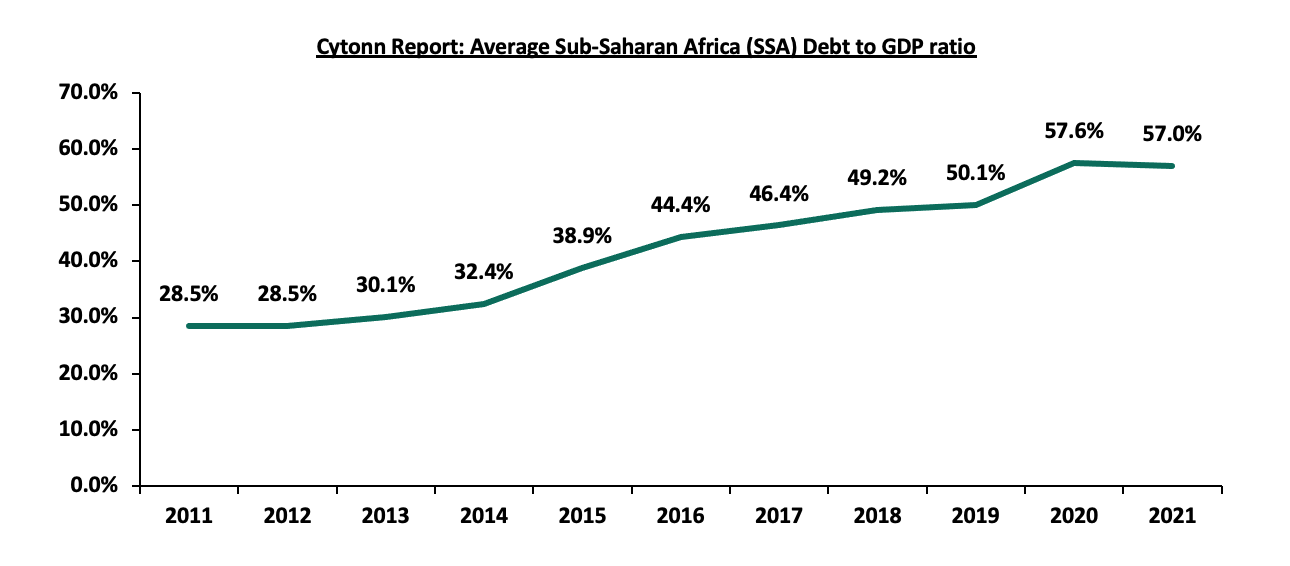

Debt sustainability has been a cause for concern within the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region and has been aggravated by a slow post pandemic recovery, elevated inflationary pressures and a backdrop of depreciating currencies in 2022. According to the Joint World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) as of September 2022, eight countries in the region are identified as in debt distress while 14 are at high risk of debt distress, and 16 at moderate risks of debt distress. Additionally, according to the Bloomberg Global default risk index 2022, for the SSA countries, Ghana and Kenya are ranked 1st and 2nd , respectively, pointing towards increased perceived risks on their debt sustainability. This has been mainly on the back of poor fiscal and monetary policies in most countries in the Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) region resulting to its debt to GDP ratio almost doubling to 57.0%, 7.0% points above the IMF recommended threshold for developing economies at the end of 2021 from 28.5% recorded in 2011. The graph below shows the evolution of the average debt to GDP ratio in the Sub- Saharan Africa (SSA) region for a period of 10 years;

Source: IMF

The rapid increase in the Public debt to GDP ratio points that the public debt accumulation is not being matched by economic growth, making it unsustainable and leading to more countries being on the verge of debt distress. Eventually, restructuring becomes a matter of inevitability as the Governments have to carry out social functions like health and education services, while at the same time servicing debt. Ghana, like many other developing countries, has accumulated high levels of public debt to a point of unsustainability. Consequently, the World Bank ranks both risks, external debt distress and risk of overall debt distress for Ghana as high, an indication of high probability of debt repayment default and that, the rising debt burden needs careful management. As a result, the government of Ghana initiated a debt restructuring in December 2022, in order to restore its capacity to service its public debt as well as improve its local business environment;

In a bid to understand the looming economic crisis in Ghana due to its high debt levels, we shall analyze Ghana’s debt trends over time and the look at the debt restructuring initiative taken by its government to restore macroeconomic order as follows;

- Ghana’s Macroeconomic environment,

- Evolution of Ghana’s public debt,

- Ghana’s Debt Restructuring,

- IMF Lending Facility to Ghana,

- Challenges faced by Ghana’s debt restructuring program, and,

- Conclusion

Section 1: Ghana’s Macroeconomic Environment

Ghana has been a major driver of economic growth in both the West and Sub Saharan Africa, driven by the high exports of agricultural products such as cocoa. However, its reliance on imports such refined oil and gas imports and its high public debt to GDP ratio have led to the deterioration of the Ghana’s macroeconomic environment, as discussed below;

- Economic Growth

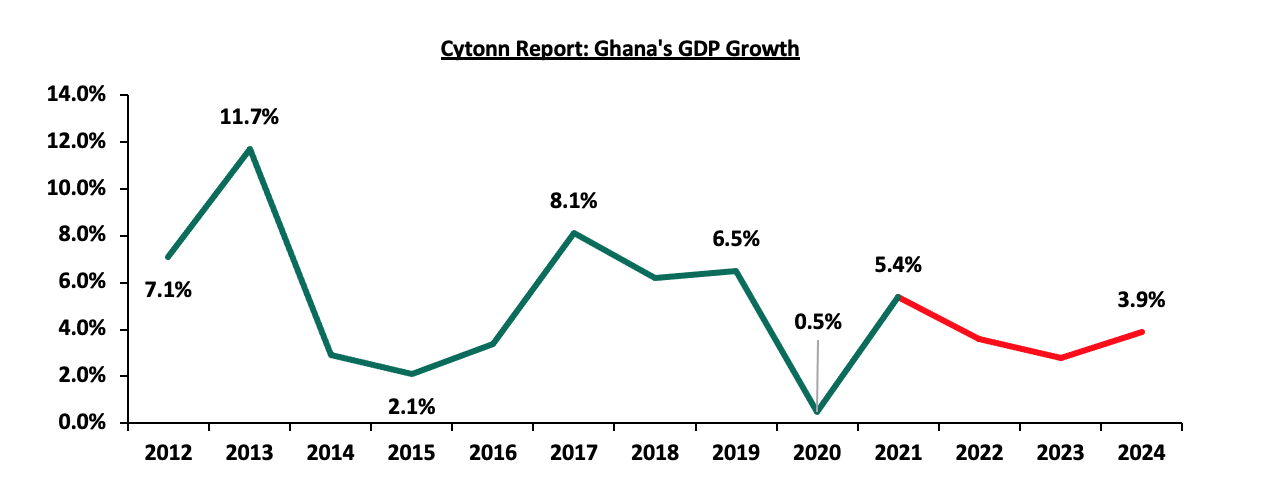

According to the World bank, Ghana’s Gross Domestic Product grew by a 10-year CAGR of 7.0% to USD 77.6 bn in 2021 from USD 39.3 bn recorded in 2011. This has been driven by the diversification of the economy, led by the growth in the services sector, which accounted for 48.9% of GDP in 2021, whose back bone is the information and communication sub sector. The industrial sector and the agricultural sector contributed 30.1% and 21.0% of GDP, respectively, in the same period. Additionally, the economy expanded by 5.4% in 2021 from the 0.5% expansion in 2020 mainly due to the post pandemic economic recovery. However, Ghana’s GDP growth is forecasted to slow to 3.6% in 2022 and decline further to 2.8% in 2023 on the back of elevated inflation following the high global fuel and food prices. The graph below shows the Ghana’s GDP growth rate for the last 10 yrs;

Source: IMF

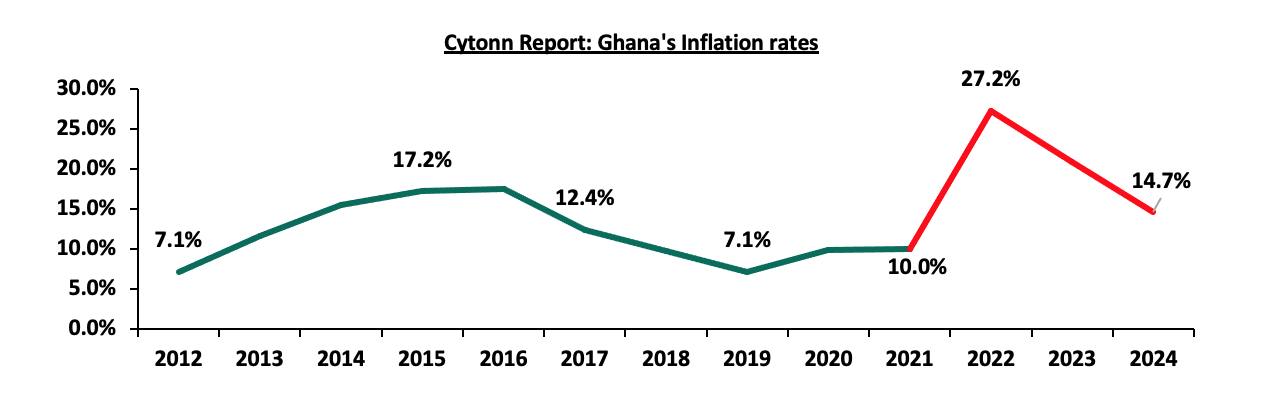

- Inflation

Ghana’s y/y inflation hit a record high of 50.3% in the month of November 2022, a 9.9% points increase from 40.4% recorded in October 2022 driven by the 79.1% increase in the prices of housing, water, gas and electricity, and 63.1% increase in the prices of transport and fuel. Notably, this is the highest inflation rate recorded in the last 21 years. On an annual basis, according to the IMF, the inflation is projected to close the year at an average record high of 27.2% from 10.0% recorded in 2021, significantly higher than the government’s target of the range of 6.0%-10.0%. The graph below shows the Ghana’s inflation rate for the last 10 years;

Source: IMF

- Currency

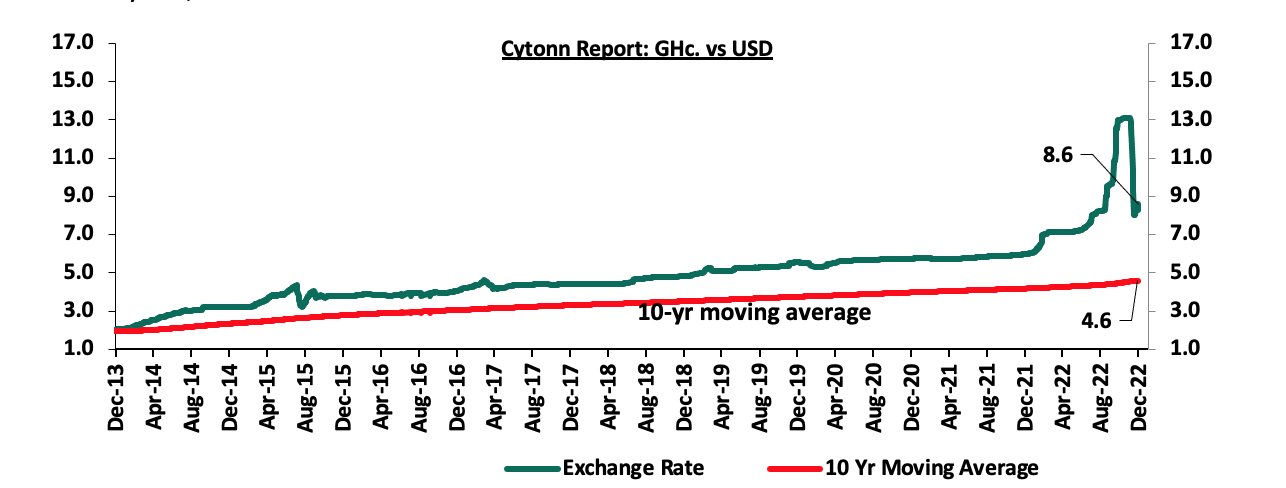

In 2022, the Ghanaian Cedi depreciated by 42.8% to close at Ghc 8.6 recorded on 30th December 2022 from Ghc 6.0 recorded against the U.S dollar on 4th January 2022 to become the worst performing currency in Sub Saharan Africa. This was mainly attributable to the high debt servicing costs and import reliance, with the currency reserves declining by 32.0% to USD 6.6 bn in September 2022 from USD 9.7 bn in December 2021, representing 2.9 months to import cover. The graph below shows the movement of the Ghanaian Cedi for the last 10 years;

Source: Bank of Ghana

- Interest Rates

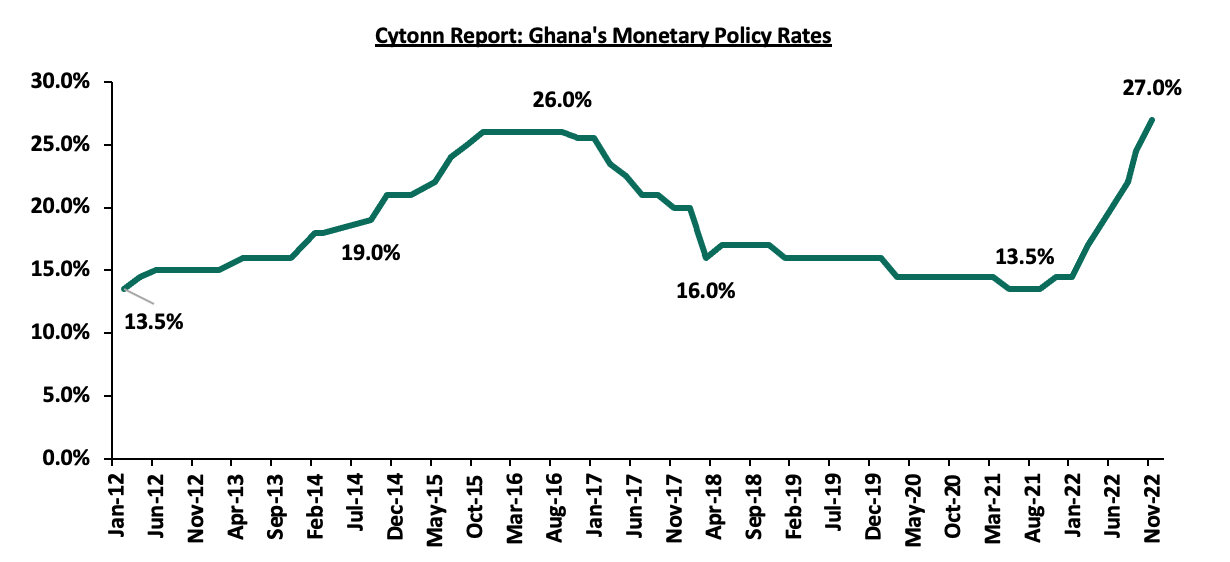

With Ghana’s Inflation rate at 50.3% in November 2022, the Bank of Ghana Monetary Policy Committee met on 28th November 2022 hiked the MPC rate by 250.0 bps to 27.0%, the highest rate recorded in the last 10 years, from 24.5% in September 2022. Despite the tightened monetary policy with five interest rate hikes in 2022, inflation continues to remain elevated driven by high dependency on imports that have been impacted by high commodity prices in the global markets. The graph below shows Ghana’s interest rates for the last 10 years;

Source: Bank of Ghana

- Current Account

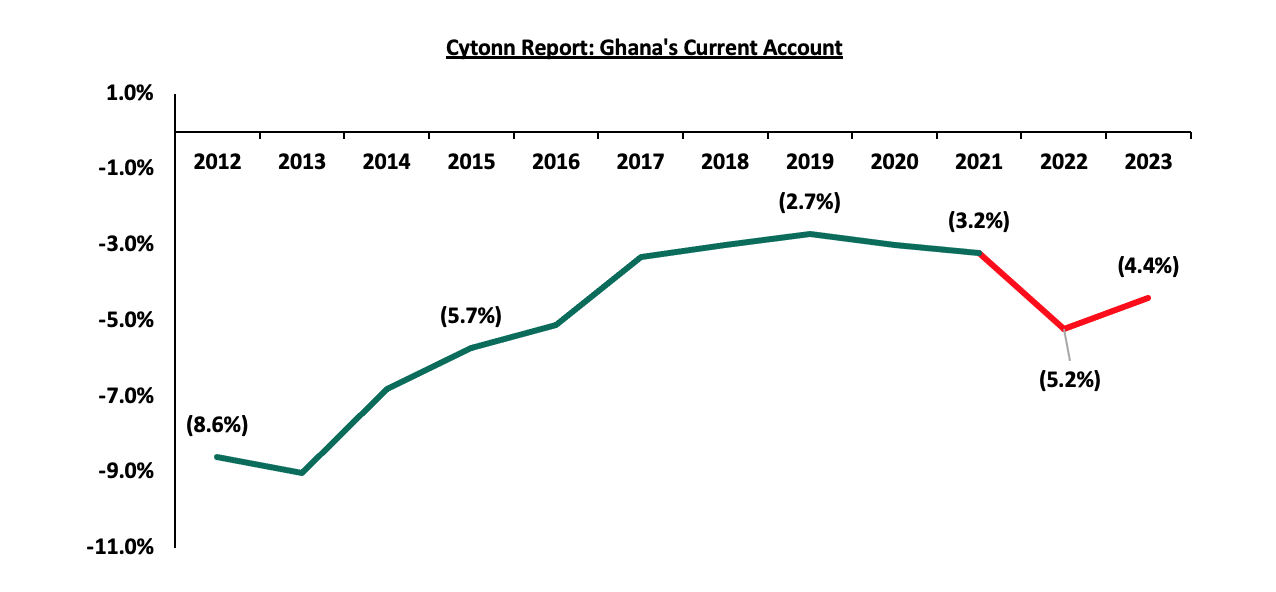

Due to the high import reliance and lack of value addition on its exports, coupled with the local currency depreciation, Ghana’s current account deficit is projected to widen further to 5.2% by end of 2022 from 3.2% in 2021, and this is expected to continue weighing down the Ghana’s economy. The graph below shows the Ghana’s current account deficit for the last 10 years;

Source: IMF

- Public Debt

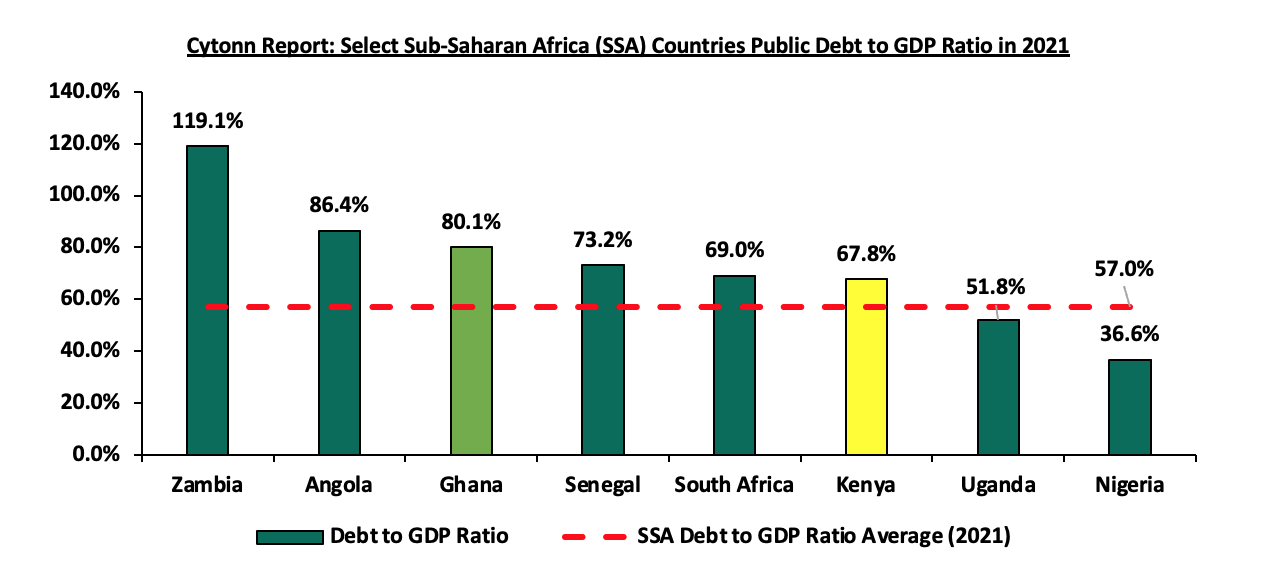

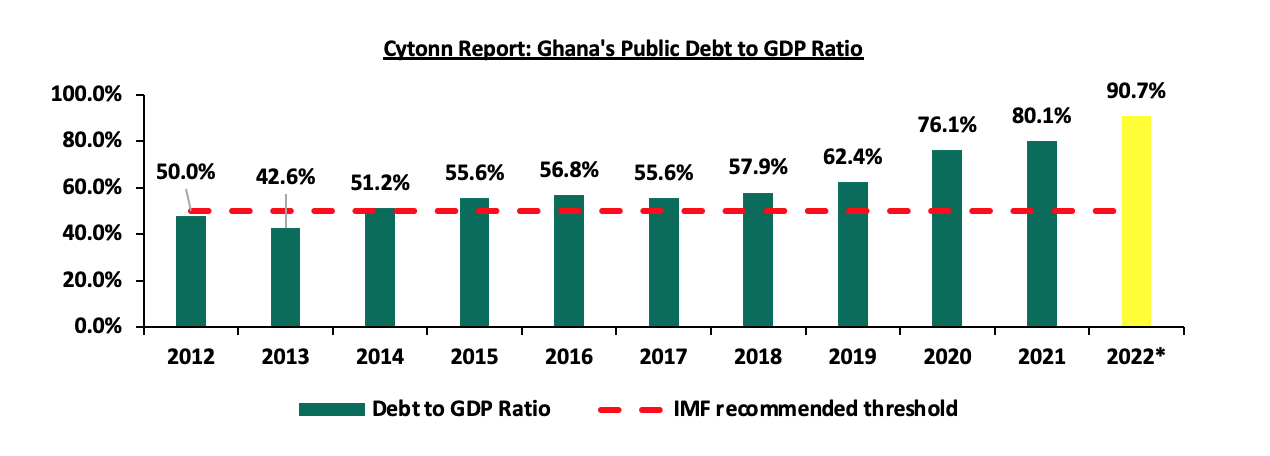

Ghana’s total public has grown with a 10-year CAGR of 14.3% to USD 58.6 bn at the end of 2021, from USD 15.4 bn recorded in 2011, on the back of rising debt appetite to cover its fiscal deficit against low revenue collections. As such, its public debt to GDP ratio came in at 80.1% in 2021, and is projected to end 2022 at 90.7%, 40.7% points above the IMF recommended threshold of 50.0% debt to GDP ratio for developing economies. Notably, according to Ghana’s Ministry of Finance, Ghana’s debt servicing costs consumed 70.0% of its tax revenues in 2022, and its public debt including debt owned by State Owned Enterprises exceed 100.0% of its GDP in the same period, presenting a hard challenge to the government to balance between debt servicing and economic development. Ghana’s public debt to GDP ratio at 80.1% in 2021, is 23.1% points higher than the SSA average of 57.0%. The graph below shows a comparison of the debt to GDP ratio of select Sub-Saharan Africa economies as of the end of 2021,

Source: IMF, Bank of Ghana

The above factors highlight Ghana’s tough macroeconomic environment which when coupled with a deterioration in the business environment have further deepened Ghana’s debt distress, with the government lagging behind in its revenue collection targets.

Section II: Evolution of Ghana’s Public Debt

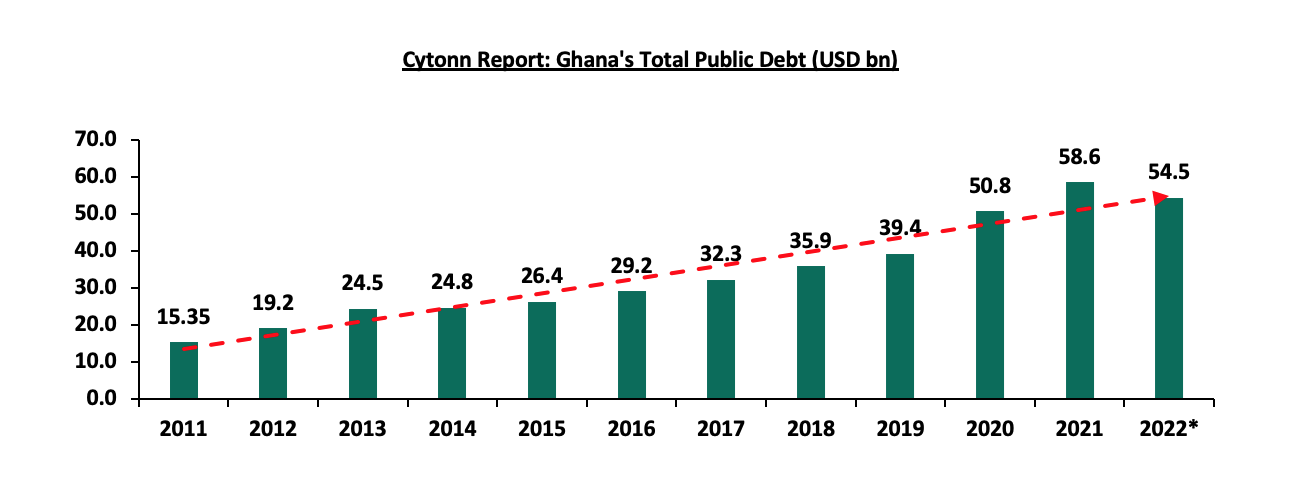

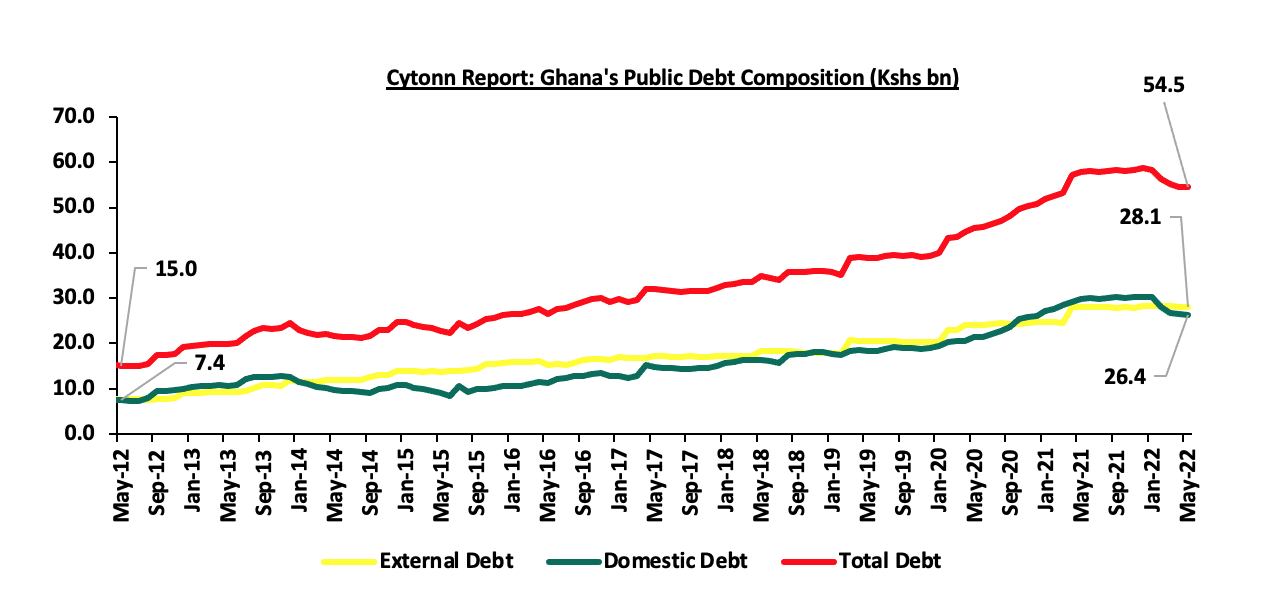

Ghana’s public debt has been on the rise, having grown with a 10-year CAGR of 14.3% to USD 58.6 bn in 2021 from USD 15.4 bn the end of 2011, representing 80.1% debt to GDP ratio, above the 70.0% debt to GDP ratio threshold recommended by the Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS) and the IMF recommended threshold of 50.0% for developing economies. Notably, Ghana’s public debt recorded a 29.1% increase to USD 58.6 bn in 2021 from USD 50.8 bn in 2020, mainly attributable to spillover effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that saw a slowdown in exports and economic activity, coupled with the financial and energy sector bailouts. Ghana’s fiscal deficit has continued to heighten to 11.7% in 2021, from 9.6% of GDP in 2020, mainly attributable to a challenging macroeconomic environment that has continued to weigh down on revenue collection. As of May 2022, the country’s public debt came in at USD 54.5 bn, equivalent to 77.5% debt to GDP ratio. The graph below shows the evolution of Ghana’s public debt over the last 10 years;

*Figures as of May 2022, Source: Bank of Ghana (BoG)

According to the IMF, Ghana’s debt to GDP ratio is projected to grow to 90.7% by the end of 2022, on the back of high borrowing levels that outweigh economic growth. This is excepted to cause a debt overhang that will lead to crowding of the private sector. The graph below shows Ghana’s debt to GDP for last 10 years;

*Figures as at May 2022, Source: Bank of Ghana, IMF

Over the last 10 years, the Ghana’s external debt has grown with a 10-yr CAGR of 14.0% to USD 28.1 bn as at May 2022 from USD 7.6 bn in May 2012, while its domestic debt grew by a slower CAGR of 13.5% to USD 26.4 in May 2022 from USD 7.1 bn recorded by the end of May 2012. As such, Ghana debt mix shifted to 49:51 domestic to external debt as at May 2022, from 50:50 in May 2012. The graph below shows Ghana’s domestic and external debt composition for the last 10 years;

Source: Bank of Ghana

Ghana’s Global Credit Ratings

The following is a summary of the Ratings on Ghana from the three main Global Ratings agencies in 2022,

- S&P Ratings- In December 2022, Standard and Poor (S&P) Ratings downgraded Ghana’s Long Term Currency bonds to ‘selective default’ and also downgraded the country’s foreign currency debt to ‘CC’ from ‘CCC+’ in August 2022. This was majorly attributable to the proposed Domestic Debt Exchange Programme, which S&P noted to be a distressed exchange offer, a likelihood that institutional investors would incur some losses during the debt restructuring process,

- Fitch Ratings- Fitch Ratings also downgraded Ghana’s Long-Term Local-Currency (LTLC) Issuer Default Rating (IDR) to ‘C’ from ‘CC’ in September 2022 and ‘CCC’ in August 2022. Fitch attributed the downgrade to the Domestic Debt Exchange Program (DDEP) to be like a default initiation process, and,

- Moody’s Ratings- Moody’s downgraded Ghana’s Long-Term Issuer and Senior unsecured bond ratings to ‘Ca’ from ‘Caa2’, however assigned a stable outlook, as creditors would incur losses in the proposed debt restructuring program.

The continued downgrading of the Ghana’s economic outlook by the three agencies during the year pointed towards the looming economic crisis in Ghana, leading to a decline in investors’ confidence in its economy. Additionally, the deteriorated credit ratings have continued to limit Ghana’s access to the international sources of financing, and increasing trading yields on Eurobonds, and therefore translating to high external debt servicing costs.

Section III: Ghana’s Domestic Debt Restructuring

- Initial Debt Restructuring

The government of Ghana in October 2022, formed a five-member committee and began working on a debt restructuring program, which was announced by the Deputy Minister for Finance towards the end of November 2022, the initial debt proposal involved:

- International Bondholders- They would undergo a 30.0% haircut on their principal investments coupled with forgoing some interest payments,

- Domestic Bondholders- With majority of domestic bondholders being commercial and custodian banks, they would also forgo some interest payments, and also have their bonds exchanged by new ones that would offer no coupons in the 1st year, 5.0% in the second year and 10.0% in the third year, and,

- Foreign bonds- The government highlighted that it would suspend coupons on foreign bonds for three years.

- Current Debt Restructuring Plan

On 4th December 2022, the Government of Ghana, through its Ministry of Finance announced the new Domestic Debt Restructuring Plan, named the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP) which came into effect on 5th December 2022. The program involved:

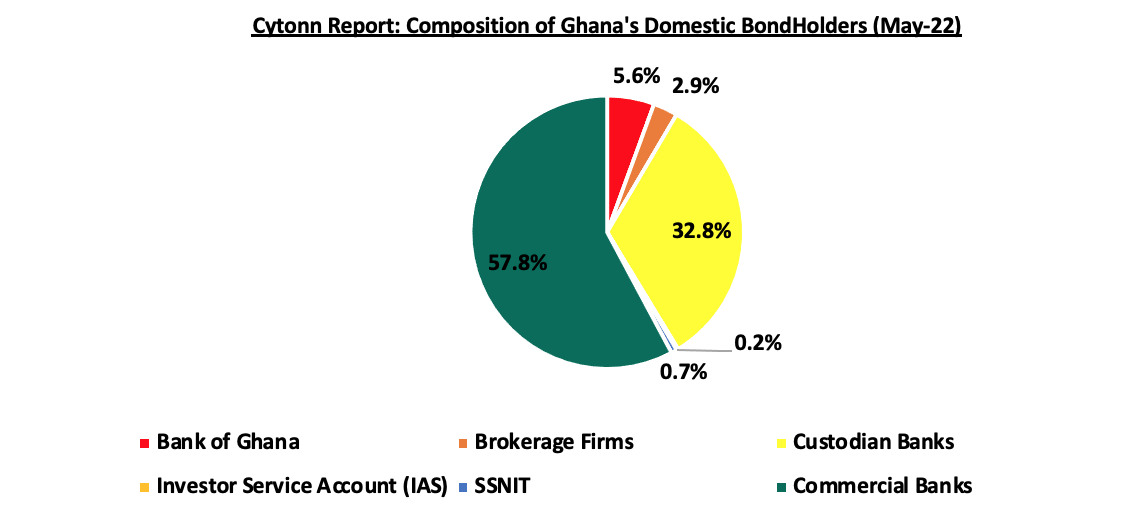

- Domestic Debt Exchange- The Programme involved the exchange of the local currency denominated bonds as at 1st December 2022 with new bonds with maturities in 2027, 2029, 2032 and 2037 and annual coupons for the new bonds set at 0.0%, in 2023, 5.0% in 2024 and 10.0% from 2025 till maturity. The allocation ratio was set at 17.0%, for the short bonds maturing in 2027 and 2029, 25.0% and 41.0% for the bonds maturing in 2032 and 2037, respectively. The move was designed to give the government time to stabilize the domestic economy and in turn improve the business environment for investors consequently increase government revenue collection. The graph below shows the different holders of government’s bonds as of May 2022,

Source: Ghana’s Central Securities Depository - Financial Sector Impact Minimization- In order to minimize the impact of the domestic debt exchange programme on small investors, individuals and other vulnerable groups, the ministry noted that T-bills would be excluded in the exchange programme, with a commitment of payment of full value amount at maturity. Additionally, there would be no haircut as earlier proposed in the initial debt restructuring plan, and individual bond holders will be fully exempted from the programme. The Government also called for all regulatory bodies such as the Bank of Ghana, The Ghana Securities and Exchange Commission, the National Insurance Commission and the National Pensions Regulatory Authority to put measures to reduce the impact of the programme on the sector, and,

- The Financial Stability Fund (FSF)- Additionally, the government would establish a Financial Stability Fund (FSF) that would act as last resort to the financial sector, and would back up the liquidity to all financial institutions such as commercial banks, pension funds, insurance companies, fund managers and Collective Investment Schemes (CIS) to ensure that they are able to pay their clients once maturities fall due. The FSF had a target of USD 1.2 bn to be raised from the World Bank and other financial institutions.

The programme would involve an exchange of approximately GhC 137.3 bn (USD 10.5 bn) of the existing domestic bonds with fresh bonds, as the government would not be able to service the debt without restructuring. The program was set to commence on 5th December 2022 and close on 19th December 2022, but would be extended at the decision of the government.

In a bid to ensure the stability to banks during the DDEP, the Bank of Ghana published the regulatory reliefs that would take effect on 23rd December 2022, and included:

- For the local currency deposits, there would be a reduction of the Cash Reserve Requirement (CRR) to 12.0% from 15.0% while for the foreign currency denominated deposits, the CRR would be maintained at 12.0%,

- A reduction of the Capital Conservation Buffer to 0.0% from 3.0% and therefore, reducing the Capital Adequacy Ratio CAR to 10.0% from 13.0%. Additionally, risk weights attached to the new bonds will be set at 0.0% for CAR computation and 100.0% for the old bonds,

- While determining the financial exposure of banks to counterparties, new bonds will be fully deductible while old bonds will not, and,

- Increase in Tier II banks component of regulatory capital to 3.0% from 2.0% of the total risk weighted assets and also increase in allowable portion of the property revaluation for Tier II banks capital computation to 60.0% from 50.0%, and this would ensure that small banks were well capitalized to withstand the DDEP shocks.

Furthermore, banks would be required to submit data on liquidity ratios, their access to interbank markets, and their cost of financing on a daily basis to the Bank of Ghana, and also the banks would access the reverse repos provided by the new bonds to boost liquidity. All banks would also pre-position their assets for eligible collateral under the Central Bank’s Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA), which would be accessed with other collaterals excluding the old bonds, and the banks would not declare or pay any dividends to their shareholders. However, Fitch noted that it expects that many Ghanaian Banks to face significant pressure on their capitalization, and suffer economic losses for exchanging their existing debt for the new bonds with lower coupons and longer tenors. Nevertheless, Fitch noted that it believed on the Bank of Ghana’s new regulatory measures to cushion the banks against the financial impact of the exchange program will be sufficient to enable the local banks mitigate the impact.

- Reception of the Debt Restructuring from stakeholders

Due to the announcement that bondholders who have invested through financial institutions such as banks, investment companies, pension schemes and insurance companies, would be required to exchange their bonds, many financial institutions announced their rejection to the exchange program;

- Local pension firms, which hold 5.6% of Ghana’s domestic bonds, and since they are mandated by the Ghana’s Pension Regulatory Authority to have majority of their assets in government securities, poised their concerns on the prolonged maturity timelines,

- Six Labor unions including the Ghana Registered Nurses and Midwives Association (GRNMA) and the Chamber of Corporate Trustees (CCT) issued their directive rejecting the exchange programme on 6th December 2022, and,

- The Ghana Securities Industry Association (GSIA) also announced their rejection to the domestic bond exchange program, as they were not involved during the engagements to unveil the restructuring exercise.

The negative reception of the majority of the bondholders presented a challenge to the government, and in a bid to ease the exchange programme the government has been updating the proposal as follows;

- Extension of the exercise duration- The government has extended the closing date of the exchange programme twice from the initial date of 23rd December 2022 to 30th December 2022 and later to 16th January 2023 in order to give more time to the financial sector institutions to secure the necessary approvals for their involvement in the exchange programme,

- Exempting Pension Funds from the programme- The government announced that it will drop pensions firms from the ongoing domestic debt exchange programme, and that, the parties involved would engage to prepare an alternative plan,

- Paying accrued and unpaid interest on eligible Bonds-The government announced that it would pay accrued and unpaid interest on eligible bonds and a cash tender fee payment to holders of eligible bonds maturing in 2023. Additionally, interest on the new bonds will not accrue until 2024, but will start paying the interest at a rate of 5.0% after 2024, increasing to 10.7% for the new bonds that will mature in 2038,

- Increasing the new bonds under DDEP program to twelve from the initial four bonds-The government added 8 new bonds with one maturing every year from 2027 to 2038,

- A modification to the Exchange Consideration Ratios- The Exchange Consideration Ratio applicable to Eligible Bonds maturing in 2023 will be different than for other Eligible bonds. The table below shows the new consideration ratios;

|

Cytonn Report: Ghana’s New Exchange Consideration Ratios |

|||||||||||||

|

Eligible Bond Tendered |

2027 |

2028 |

2029 |

2030 |

2031 |

2032 |

2033 |

2034 |

2035 |

2036 |

2037 |

2038 |

Cash Tender Fee* |

|

Eligible 2023 Bonds |

15.0% |

15.0% |

14.0% |

14.0% |

14.0% |

14.0% |

14.0% |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

2.0% |

|

Eligible Post 2023 Bonds |

9.0% |

9.0% |

9.0% |

9.0% |

8.0% |

8.0% |

8.0% |

8.0% |

8.0% |

8.0% |

8.0% |

8.0% |

N/A |

|

*As a percentage of principal amount of the tendering eligible Holder’s Eligible 2023 Bonds |

|||||||||||||

- A non-binding target of 80.0%- The government set a non-binding target minimum level of overall participation of 80.0% of the aggregate principal amount outstanding of Eligible Bonds, and,

- Including Individual Bond holders- Rather than only applying the exchange to institutional bond holders, the government announced the expansion of the program to cover even individual investors.

- IMF Lending Facility to Ghana

The first International Monetary Fund (IMF) visit to Ghana in a bid to discuss a lending arrangement with Ghanaian Authorities was held between 6th -13th July 2022. During the visit, the IMF noted that the current fiscal deficit and debt situation in Ghana was adversely impacting on the economy of Ghana, and that, a credit package would be needed to restore macroeconomic stability. This was followed by other two visits in October and November 2022. Notably, on 12th December 2022, the IMF announced that it had reached a staff level Agreement on a 3-year program of the Extended Fund Facility (ECF) amounting to USD 3.0 bn (SDR 2.2 bn) which was subject to the IMF management and Executive approval, and after the receipt of the necessary commitments from Ghana’s partners and Creditors. Therefore, the Ghanaian authorities agreed to reforms which include:

- Develop a medium term plan to generate additional revenue and increasing tax compliance,

- Strengthening commitment controls on public expenditure,

- Enhancing the reporting and monitoring of expenditures that would promote transparency,

- Improving the management and running of state owned enterprises, and,

- Addressing structural challenges in the energy and cocoa sectors.

The agreement followed the launch of the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme, which IMF noted that its progress would be needed before the approval of the facility. This partially increased confidence in their economy and consequently the Cedi appreciated by 34.6% to close the year at GHc 8.6 from the adverse exchange rate of GHc 13.1 against the U.S Dollar recorded on 17th November 2022.

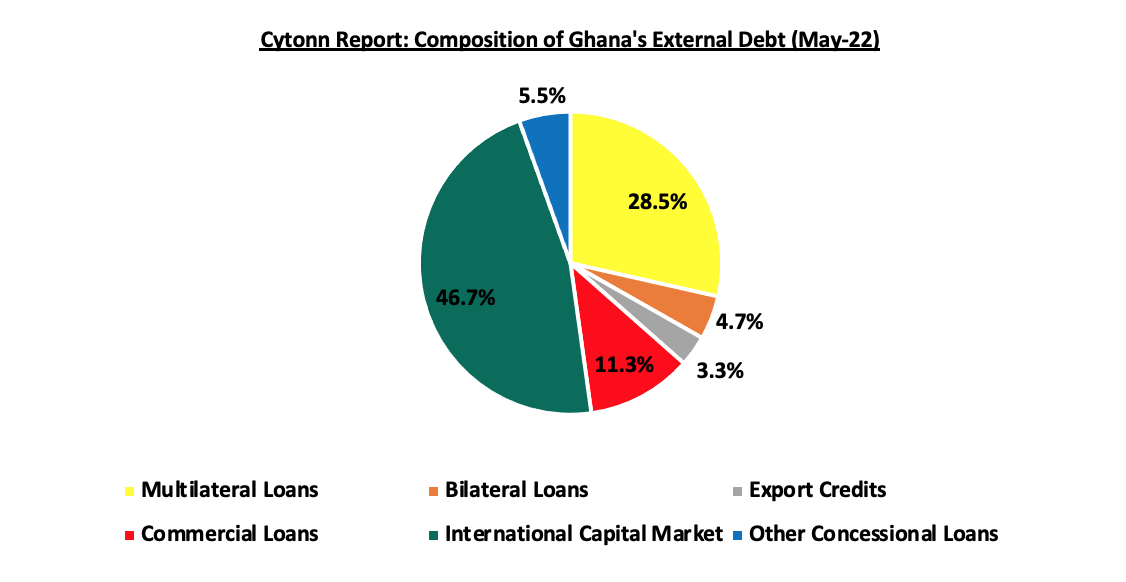

- External Debt Restructuring

As an interim measure to prevent the further deterioration of Ghana’s financial and economic situation, Ghana’s Ministry of Finance announced a suspension of all external debt servicing payments, from 19th December 2022. The suspension would include the servicing of Eurobonds, commercial loans, and most of the bilateral loans, while excluding the suspension of servicing of multilateral debt and new debts contracted after 19th December 2022 and debts related to certain short term trade facilities. This move was taken before an orderly restructuring program was initiated, leading to further deterioration of the country’s credit risk ratings. As at the end of May 2022, International capital markets, which include the Eurobonds, at USD 13.1 bn formed the majority of Ghana’s external debt, representing 46.7%, with Ghana issuing 16 Eurobonds in the last 10 years. As such, on 19th December 2022, holders of Ghana’s Eurobonds formed a committee to formulate an equitable restructuring proposal, which was aimed to restore credit worthiness in the economy. The chart below shows the composition of Ghana’s external debt as at end of May 2022;

Source: Bank of Ghana

Section V: Challenges undermining the success of Ghana’s Domestic Debt Exchange Programme

There are several factors that continue to barricade Ghana’s efforts to have a successful debt exchange program. This include;

- Lack of all-round stakeholder engagement- Evidenced by the negative reception by many of the stakeholders in its domestic bond holders, coupled extension of the expiration date twice and the adjustments made to the current debt restructuring program, the exchange program lacks an all-inclusive shareholder’s perspective. Key to note, the debt restructuring committee is made up of only the Ministry of Finance and Bank of Ghana excluding recipients of the program, in this case the bond holders from vital decision making processes of the debt exchange program. In a debt restructuring of such magnitudes, the government should have formed a committee where all stakeholders are represented, in order to gain trust from all the parties involved,

- High losses to investors- It is clear that in the current debt restructuring program that the government wants to shift too much of the burden to the investors. Taking into account the 2038 due date for the maturity of the long term instruments, Ghanaian investors are going to lose 55.0% of their T-bonds investments, representing only 45.0% recovery rate, lower than the 52.0% recovery rate on previous debt restructuring occasions such as Greece and Grenada at 65.0% and Grenada 50.0%, respectively,

- Lack of Credit enhancements in the new exchange instruments – In addition to the low recovery rate to the investors, Ghana’s new debt instruments will not pay interest in 2023, extinguishing any form of liquidity due to unattractiveness of the bonds. The new instruments can be enhanced by, for instance, guarantees backed by international bodies or higher coupon rates to make up for upfront losses, and,

- Absence of a strong legal framework- The lack of a proper legal framework has weighed down the Ghana’s debt exchange program. This is evidenced by the prompt formulation of guidelines, only to be amended a few days later.

Section VI: Conclusion

Majority of Sub-Saharan countries continue to suffer from high debt levels that push their economies to levels of crisis. In addition to Ghana’s debt restructuring, we have seen Kenya recently pursue a voluntary switch bond issue in June 2020 and in December 2022, where holders of short-term debt valued at Kshs 25.6 bn and 87.8 bn, respectively, were given an option to switch to a longer term debt of 6 years for each of the two switch bonds. As such, the switch bonds received an overall subscription rates of 82.7% and 60.3%, respectively, while the rest opting to be paid upon maturity. In Nigeria, the Government sent a proposal to parliament in December 2022 for approval to allow for a restructuring of USD 54.0 bn, short term loans owed to its Central Bank to a 40-year security at an interest of 9.0%. Additionally, Zambia initiated an external debt restructuring exercise in 2022 under the Common Framework for Debt Treatment of the G20, after a sovereign default in 2020 due to high debt unsustainability.

Therefore, the governments should put in place measures that promote high revenue collection rather than relying on public debt to cover their fiscal deficits. Below are some of the measures that Sub-Saharan countries can put in place to evade high levels of risk distress;

- Enhance fiscal consolidation- The mismatch between higher public expenditure and the lower revenue collections has continued to expand fiscal deficits necessitating borrowing. To offset such imbalances, the SSA countries need to either cut on government recurrent expenditures, or increasing revenue performance to promote fiscal consolidation,

- Addressing the structural and financing challenges faced by State Owned Enterprises (SOEs)- Majority of SOEs continue to record losses due to poor governance policies and depend heavily on government bailouts. One of the ways to reduce the burden from SOEs is to privatize them in order to bring them,

- Export Promotion- The SSA economy, which is majorly agriculturally and service driven, has for years lacked value addition to its exports, which results to low revenues from exports. The governments should promote export value addition structures such as the Export Processing Zones and industrialization, as this would increase the value of its exports, boosting their foreign exchange reserves. This would not only improve the region’s GDP but also anchor currency depreciation and reduce the costs of servicing of foreign currency denominated loans,

- Encouraging alternative means of financing infrastructure such as Private Public Partnerships (PPPs)- Infrastructure projects are capital intensive and majority have been funded through Public Debt. The governments should promote and streamline alternative means of financing such as PPPs and joint ventures in development projects,

- Putting in place measures that spur economic growth- Such measures that increase economic output include tourism, entrepreneurship, technology and innovation, as well as easing regulations that encourage favorable business environment, and,

- Restructure public debt early if need be- Countries in SSA that have high debt levels should restructure their debts instead of waiting to fall into debt distress. The following three countries have initiated forms of debt restructuring;

-

- Kenya- In June 2020 and December 2022, the Kenyan Government offered switch bonds for holders of government T-bills to voluntary switch to two Infrastructure bonds namely; IFB1/2020/6 and IFB1/2022/6, with tenors to maturity of 6 years each. The bonds received overall subscription rates of 82.7% and 60.3%, for IFB1/2020/6 and IFB1/2022/6, respectively, with the rest of the T-bill holders opting to hold and be paid upon maturity. This came at a time when the yields of the government papers have been on an upward trajectory, gaining by 6.1 bps, 1.3 bps and 2.3 bps to 10.4%, 9.8% and 9.4% for the 364-day, 182-day and 91-day papers respectively, for the first week of 2023,

- Zambia- Initiated restructuring of its public debt in 2022 which involved forming a creditors committee that included all external lenders under the Common Framework for Debt Treatment of the G20. This after defaulting on its sovereign debt in 2020 and its debt to GDP ratio coming in at 140.2% in 2020 pointing towards debt distress. This came after the USD 1.3 bn IMF assistance in August 2022, in which the debt restructuring was needed for the credit assistance to be approved, and,

- Nigeria- In our 2022 annual markets review, we highlighted that Nigeria Government had sent a proposal to parliament for approval to allow for a restructuring of USD 54.0 bn, short term loans owed to its Central Bank to a 40-year security at an interest of 9.0%. The debt was incurred through Ways and Means Advances to finance government deficit as a result of delayed government receipts. The Nigerian Executive also requested for a three-year moratorium on interest payments on existing debts and asked for another USD 2.2 bn (N1.0 tn) debt from Central bank on similar terms.

Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring success is pegged on its reception to the bondholders, since it is a voluntary exercise. As such, we expect the Government of Ghana to extend the exercise dates from the stated expiration date of 16th January 2023, and this will further delay the IMF assistance since it is one of the conditions that the government should implement before the credit assistance. However, we commend the government of Ghana for initiating the debt restructuring, but there is the need of all parties, especially the financial institutions, to be engaged for the success of the exercise. Broadly, we expect more public debt restructuring initiatives to be taken by other SSA countries in 2023 due to debt unsustainability, worsened by the deteriorated macroeconomic environment in the region that impedes revenue collection to service debts. Closer to home in Kenya, the domestic debt accounted for 50.2% of its total public debt, with treasury bonds contributing 83.0% of the total domestic debt, with majority of the bond holders being financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies. As such, any domestic debt restructuring in the country will have greater financial impact on the financial industry. However, we commend the current administration for the measures taken to reduce the need for excessive borrowing such as partial removal of subsidies of fuel and electricity, cutting down on public expenditure, and the ongoing discussions to privatize government parastatals such as the Kenya Airways which have been debt ridden for the last 10 years and being open to renegotiate its external debt terms with external lenders. This has seen Kenya’s public debt to GDP decline to 62.3% in October 2022 from 69.1% in May 2022. However, we expect the upcoming maturity of the June 2024 Eurobond of USD 2.0 bn to increase pressure on debt servicing levels. As such, we expect further fiscal tightening by the government, complete removal of subsidies especially for fuel and an increase in the use of Private Public Partnerships rather than borrowing in development projects, as this will ease pressure on our need for excessive borrowing.