For 58 years, the Kenyan government has offered health insurance to its citizens through The National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF). The fund was established in 1966 through an act of parliament, with a core mandate of providing affordable medical insurance coverage to all Kenyans. However, years later, the state of public healthcare in the country remained below par, with inefficiencies that have led to repeated civil actions, inequality in health care provision, sub-par infrastructure, and a host of other challenges. In 2017, the Kenyan government made a strong commitment to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) as one of the Big 4 Agenda by the year 2022 and started designing and implementing priority reforms to accelerate progress. This was then picked up by the Bottom Up Economic Transformation Agenda, which also set out universal health care as one of its plans. These reforms included the following:

- Increasing the share of (mandatory) pooled resources through a health insurance-based mechanism built on the existing National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF);

- Enhancing the capacity of the NHIF to function as a strategic purchaser of health services; expanding coverage of health services equitably through an emphasis on primary healthcare (PHC); and,

- Improving public financial management (PFM) arrangements to enhance the effectiveness of public funds in the devolved health sector.

In line with these goals, on 1 May 2023, President William Ruto announced that there would be changes to the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), and in the same year, the Social Health Insurance Fund was established under the Social Health Insurance Act of 2023. The newly established fund has been scheduled to kick in as of October 1st 2024, after facing off a series of court battles in court, with the latest Court of Appeal ruling giving the fund a temporary nod. Given the public concern with this new model, we saw it fit to review the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) and shed light on its current state in terms of the milestones achieved and the challenges faced while looking at the expectations from the public. We shall also make a comparison with similar initiatives in other countries and private offers in Kenya, give our recommendations towards achieving a sustainable Fund. We shall undertake this by looking into the following;

- The State of Public Healthcare in Kenya,

- The Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF),

- The Legal Status of the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF),

- The Status of Implementation of the fund,

- Case Studies and Recommendations, and,

- Conclusion,

Section I: The State of Public Healthcare in Kenya

Through Vision 2030, the government set out to work towards universal health coverage for its citizens. Universal Health Coverage/Care (UHC) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘the ability for persons to receive the health services they need without suffering financial hardship. Over the past decade, Kenya has made major improvements in access and utilization of quality care and, as a result, on health outcomes. The cooperation between various county governments and the national government has led to an increased number of hospitals and upgrading of a number of hospitals. However, challenges still remain and the goal of a properly functioning system is still achievable but requires more work.

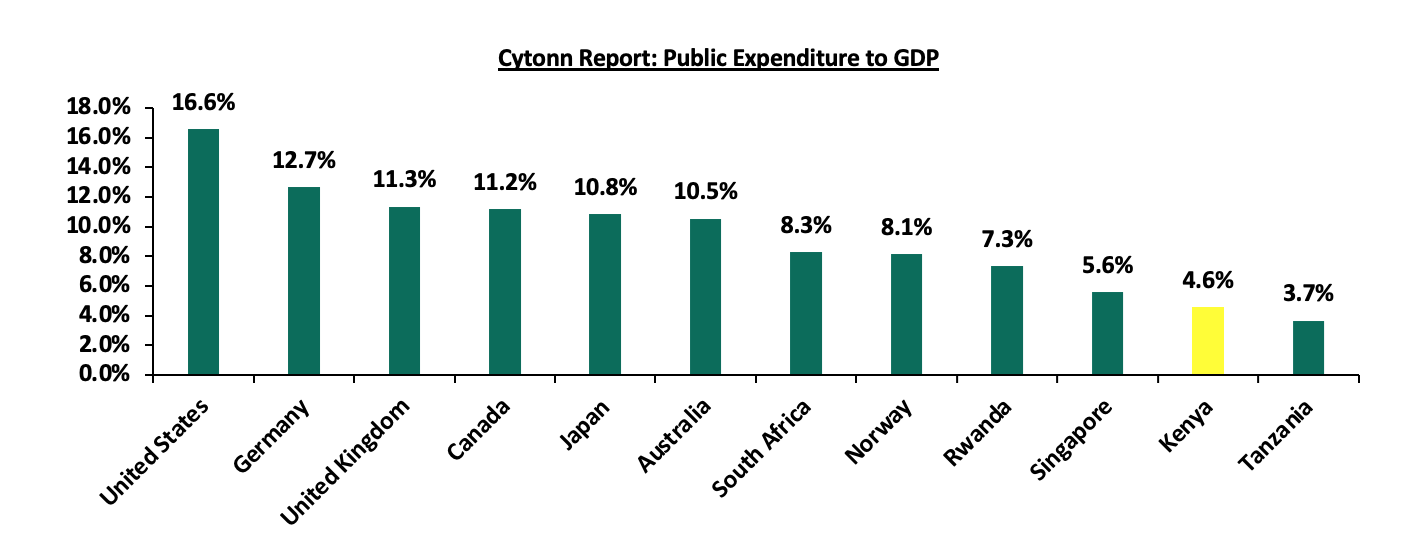

Despite the growth over the period, Kenya’s public health expenditure to GDP remains below some of its peers. This metric indicates how much the government invests in its healthcare programs relative to the size of its economy. The graph below shows this ratio, as compared to other select countries:

Source: World Bank

Kenya’s Public Health expenditure to GDP stands at a meagre 4.6%, the second lowest among select countries. Compared to countries with known working healthcare systems like Germany, Canada and Australia, there is still much that needs to be done. Achieving Universal Health Care will require a well-funded public health system that can provide equitable access to care for all citizens. With the higher unemployment and poverty rates in Kenya, which stand at 12.7% and 38.6% respectively as compared to these other countries, achieving this equality will require much more investment into healthcare than is currently being made.

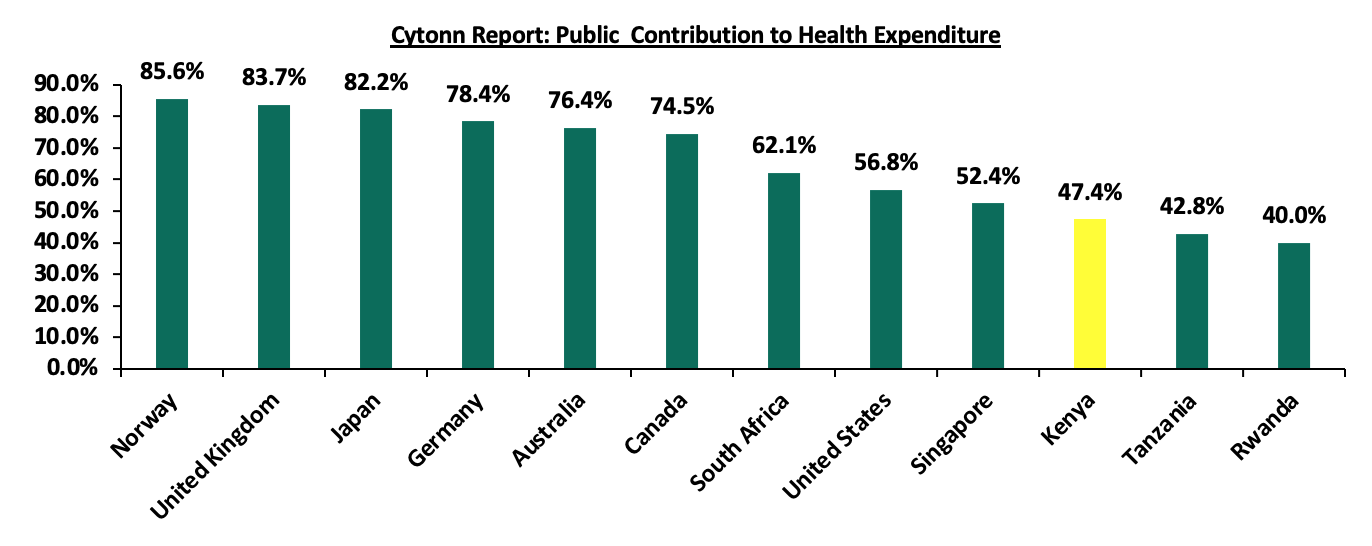

A comparison of how much of health spending in the country is covered by the government also reveals some deficiencies in Kenya’s healthcare system. Unlike some of the countries with working systems like Norway, Germany, and Australia, more than half of Kenya’s health expenditure is done through private insurance and out-of-pocket payments by individuals in the country. With a lower public contribution, the private health sector often has to fill in the gap, leading to higher costs and potentially overburdening private facilities.

Source: World Bank

In addition, Health insurance coverage in Kenya has generally been low at 26.0% according to treasury documents, with those at the bottom of the economic pyramid having the least coverage of less than 5.0%. As earlier noted, many Kenyans incur catastrophic expenditures from out-of-pocket healthcare payments, while many more do not seek care when they fall ill, because they simply cannot afford it.

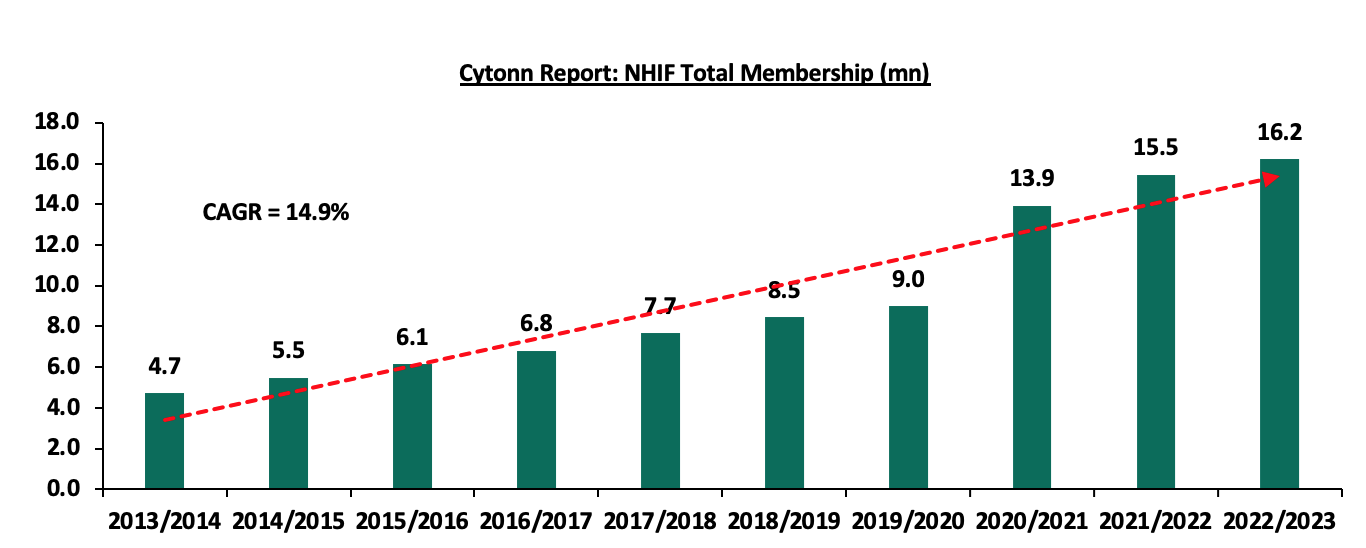

The government has offered medical insurance services to Kenyans primarily through the National Hospital Insurance Fund. As of 2023, the fund had a membership of 16.2 mn, a significant compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14.9% from the 4.1 mn in 2013, as illustrated in the table below:

The fund, however, faced a number of challenges and had gaps in its operations. Some of the notable challenges included:

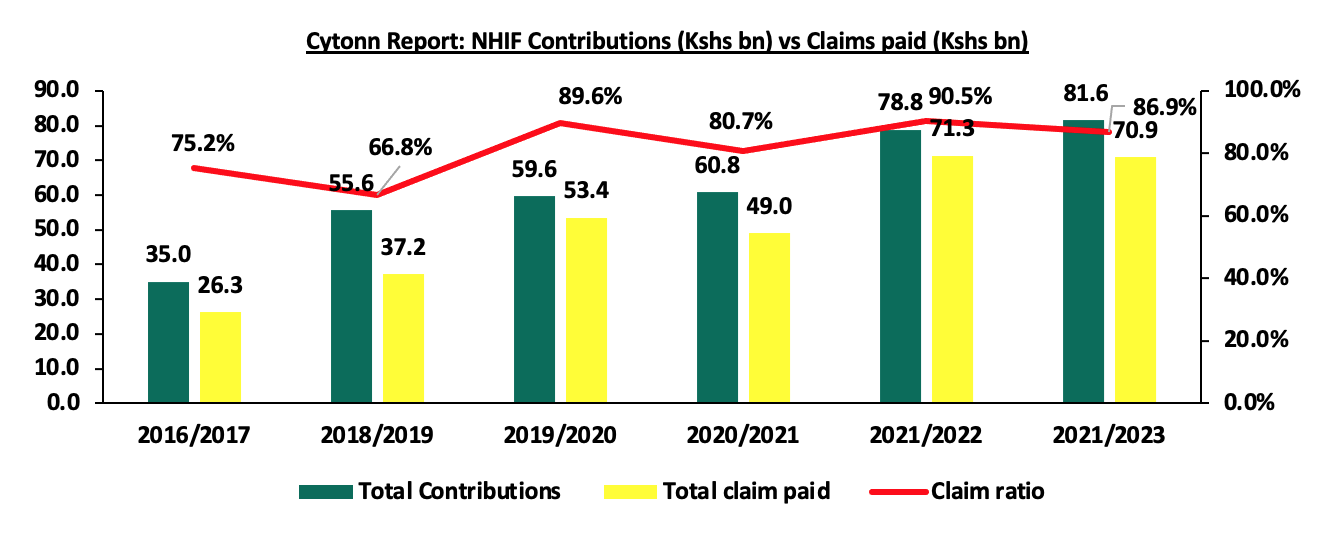

- High payout ratio - Despite the fact that NHIF premium contributions have been increasing over the years, with total contributions to the Fund growing at a 5-year CAGR of 8.0% to Kshs 81.6 bn in FY’2022/2023 from Kshs 35.0 bn in FY’2018/2019, the growth in total payout from the fund has outpaced the growth in total contribution received, having grown by a 5-year CAGR of 13.8% to Kshs 70.9 bn in FY’2022/2023, from Kshs 37.2 bn in FY’2017/2018. This has led the claim ratio for FY’2022/2023 to increase by 20.0% points to 86.9% from the 66.8% claim ratio recorded in FY’2017/2018. As such, the high pay-out ratio reduced the fund’s net operating surplus, increasing the Fund’s solvency risk and the possibility of its inability to meet future financial obligations. Below is the graph of the growth of the claim ratio for the last 5 years:

Source: NHIF Financial Statements

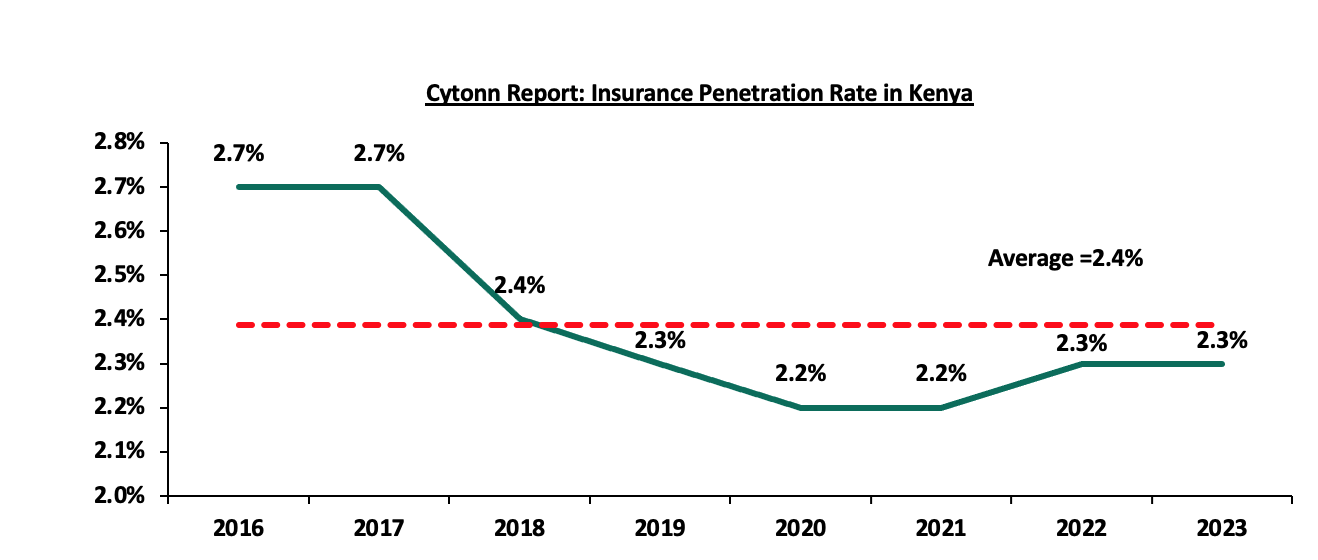

- Low Insurance Penetration – Insurance uptake in Kenya continues to remain low compared to other key economies, with insurance penetration at 2.3% as of FY’2023, according to the Q4’2023 Insurance Regulatory Authority (IRA) and the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) 2023 Economic Survey. The low penetration rate, which is below the global average of 7.0%, according to the Swiss RE institute, is attributable to the fact that insurance uptake is still seen as a luxury and is mostly taken when it is necessary or a regulatory requirement. Notably, Insurance penetration remained unchanged at 2.3% in 2023, similar to what was recorded in 2022 and 2021. The chart below shows Kenya’s insurance penetration for the last 8 years:

Source: CBK Financial Stability Reports

These challenges with the fund, together with the still underdeveloped healthcare provision in the country, made a good case for the introduction of the new fund; the Social Health Insurance Fund.

Section II: The Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF)

One of the biggest challenges about the National Health Insurance Fund that had served the country for 58 years, was that it was designed to cover only citizens with a regular income, with non-employed citizens only having to make voluntary contributions. As a result, those at the bottom of the pyramid only had a 5.0% insurance penetration rate, and a majority of them were excluded from accessing healthcare insurance. Through his Bottom Up Economic Transformation Agenda, President Ruto set out to sort this issue out through:

- providing a fully publicly financed primary health care system, an emergency care fund and a health insurance fund that will cover all Kenyans,

- installing digital health management information system,

- setting up a Fund for improving health facilities

- setting up an Emergency Medical Treatment Fund,

- establishing a National Insurance Fund that covers all Kenyans, and,

- availing medical staff who would deliver Universal Health Coverage.

In line with this, the president assented to The Social Health Insurance Act on 19th October 2023 and the Act came into force on 22nd November 2023. The Act operationalized the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), the Primary Health Fund (PHF), and the Emergency, Chronic, and Critical Illness Fund (ECCIF). The Social Health Insurance Fund would replace the existing NHIF, on the appointed day of 1st October 2024, and the NHIF would wind up within one year after this date, and transfer all its cash balances and all other assets held to the Social Health Authority (SHA).

The Social Health Authority (SHA) is the governance body that was mandated by this Act to take over all the functions and operations of the Board of National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF). The Authority consists of 11 members, including a non-executive chairperson appointed by the president, currently Dr. Timothy Olweny, and other members who include:

- the Principal Secretary of Health or a representative,

- the Principal Secretary of Finance or a representative,

- the Director–General for Health,

- a representative of the County Executive Committee Health Caucus,

- a nominee of the council of County Governors, not being a Governor, with knowledge in the field of finance, accounting, health economics, law or business and management,

- a person, not being a public officer, with proven experience in matters of health insurance, health financing, financial management, health economics, and healthcare administration,

- four persons, not being public officers, nominated by:

- the Kenya Medical Association,

- the informal sector association,

- the consortium of health providers, and,

- the Central Organization of Trade Union-Kenya.

- the Chief Executive Officer of the Authority, who is an ex-officio member of the Board.

The law mandated that SHIF would be funded by contributions from every Kenyan household, non-Kenyan residents who have lived in the country for more than twelve months, employers, national and county governments, monies appropriated by the National Assembly, gifts, grants, donations and any other innovative financing mechanisms. These contributions would be made as follows:

- Members who draw their income from salaried employment shall make contributions every month as a statutory deduction from wages or salary by the employer. The regulations proposed a rate of 2.75%, but with a floor of Kshs 300,

- Households without a salaried Income would make an annual contribution of 2.75% of their income as determined by a means testing system that would be developed, and this shall also not be less that Kshs 300, payable fourteen days before the lapse of the annual contribution,

- Households/Members that require financial assistance as determined by the set-up means testing instrument would have their contributions paid by government at a rate apportioned from the funds appropriated by Parliament and County Assemblies as prescribed, and,

- People under custody would have their contributions paid by the government at a rate apportioned from the funds appropriated by Parliament.

The table below shows a comparison of the previous NHIF contributions and the current SHIF contributions for different monthly income bands;

|

Cytonn Report: Estimated contributions from initial NHIF contribution bands |

||

|

Income Band |

NHIF Contributions |

SHIF contributions |

|

Unemployed |

Voluntary Kshs 500 contribution |

2.75% of annual income as determined by the means testing system |

|

0 - 5,999 |

150.0 |

300.0 |

|

6,000 - 7,999 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

|

8,000 - 11,999 |

400.0 |

330.0 |

|

12,000 - 14,999 |

500.0 |

330.0 - 413.0 |

|

15,000 - 19,999 |

600.0 |

413.0 - 550.0 |

|

20,000 - 24,999 |

750.0 |

550.0 - 688.0 |

|

25,000 - 29,999 |

850.0 |

688.0 - 825.0 |

|

30,000 - 34,999 |

900.0 |

825.0 - 963.0 |

|

35,000 - 39,999 |

950.0 |

963.0 - 1,100.0 |

|

40,000 - 44,999 |

1000.0 |

1,100.0 - 1,238.0 |

|

45,000 - 49,999 |

1,100.0 |

1,238.0 - 1,375.0 |

|

50,000 - 59,999 |

1,200.0 |

1,375.0 - 1,650.0 |

|

60,000 - 69,999 |

1,300.0 |

1,650.0 - 1,925.0 |

|

70,000 - 79,999 |

1,400.0 |

1,925.0 - 2,200.0 |

|

80,000 - 89,999 |

1,500.0 |

2,200.0 - 2,475.0 |

|

90,000 - 99,999 |

1,600.0 |

2,475.0 - 2,750.0 |

|

100,000 |

1,700.0 |

2,750.0 |

|

200,000 |

1,700.0 |

5,500.0 |

|

500,000 |

1,700.0 |

13,750.0 |

|

1,000,000 |

1,700.0 |

27,500.0 |

While NHIF used flat rates for different bands of income, SHIF will apply a 2.75% of the income with no maximum limit, and therefore the figures indicated on the SHIF column are the average contributions for the different income bands in the previous system.

The means testing system alluded to in the contribution methods would consider a number of parameters, including, housing characteristics, access to basic services, household composition and characteristics, and any other socio-economic aspects that may be relevant.

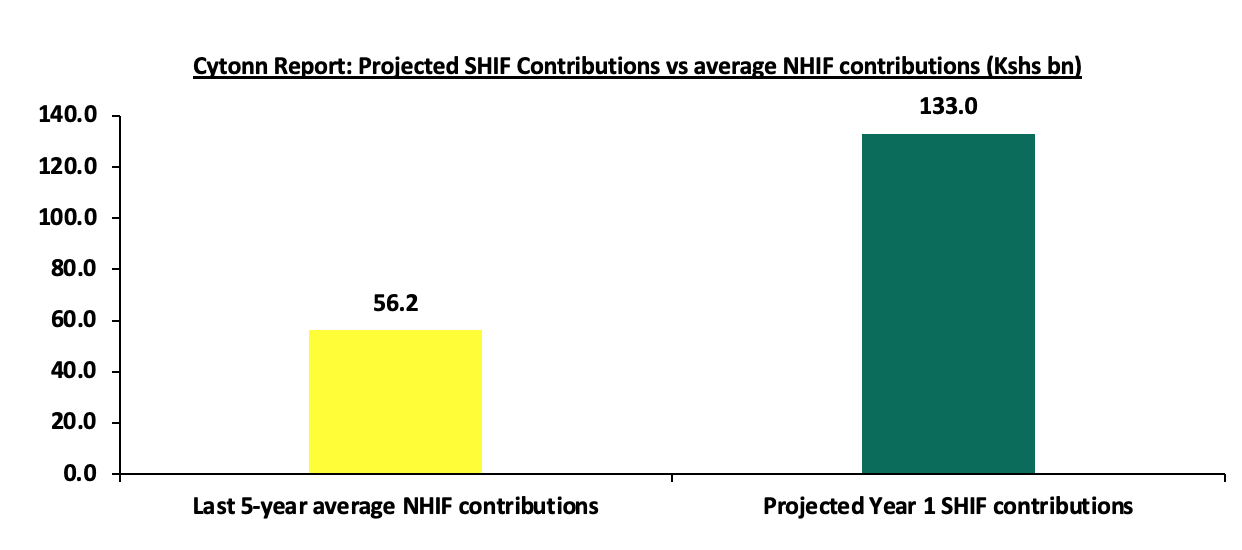

According to the Ministry of Health, this new system is projected to raise Kshs 133.0 bn annually, a significant increase from the Kshs 78.8 bn that was collected by NHIF in FY’2023/2024. The government’s aim is to use this increase to enhance coverage for the new fund. Coverage under the new SHIF is outlined in the Social Health Insurance Act.

Some key highlights from the coverage terms include:

- Outpatient Care services including consultation, lab tests, prescription processing, counselling, et cetera, are covered for all registered persons under the Primary Healthcare Fund (PCF) at a tariff of Kshs 900 per person per annum. For SHIF, outpatient cover extends to Essential diagnostic laboratory investigations for Diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases, Sickle-cell & Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)/Asthma at a tariff of Kshs 4,300, Kshs 2,850, Kshs 6,800 and Kshs 700 respectively, with a limit of once per year per person,

- Screening for common health conditions targeted screening for cancers and management of precancerous lesions will only be covered under the Primary Healthcare Fund (PCF), with different rates for different conditions to a maximum tariff of Kshs 3,600 per person,

- The Primary Healthcare Fund will also cover optical health services, including eye health education and counselling, eye tests, and treatment of refractive errors through eye glasses at a tariff of Kshs 950 per person, and a limit of Kshs 1,000.0 per household per annum. The fund will also cover end-of-life services including embalming at a tariff of Kshs 3,000.0 and storage at Kshs 500.0 per day for a maximum of five days,

- The Primary Healthcare Fund shall also cover inpatient services including hospital accommodation charges, intra-admission consultation, bedside consultations et cetera, at level 3 hospitals at a tariff of Kshs 2,240.0 with a limit of 180 days per household per annum. SHIF would then cover these services at level 4 to 6 hospitals, at a rate of Kshs 3,360.0, Kshs 3,920, Kshs 4,480 for level four, five, and six hospitals respectively up to a limit of 180 days per household per annum,

- The Social Health Insurance Fund will cover maternal, neonatal, and child health services at tariff rates of Kshs 10,000.0, Kshs 30,000.0, and Kshs 6,000.0 for normal deliveries, cesarean deliveries and anti-D serum respectively,

- The fund (SHIF) will also cover renal care services package to a limit of a specified number of sessions for different complications/conditions as outlined in the Act, tariffs for this will go to a maximum of Kshs 700,000 for recipient surgeries in transplants,

- For mental wellness benefits, SHIF will cover counselling, screening, monitoring, rehabilitation and other forms of treatment, including expenses for drug and substance abuse for up to Kshs 4,480 per person in Level 6 hospitals and rehabilitation costs of up to Kshs 67,200.0,

- The Social Health Insurance Fund will also cover medical and surgical procedures not locally available to a maximum of Kshs 500,000.0 per person per annum at overseas empaneled and contracted healthcare providers,

- For surgical services, SHIF will cover 3 minor procedures per household per year, 2=two major procedures per household per year, and 1 specialized procedure per household per year, and,

- Oral services, including oral health education, tooth extractions, suturing, and wound cleaning, shall be offered by the Social Healthcare Insurance fund with different tariffs for different conditions, but with a limit of Kshs 2,000 per household per annum, and shall only be rolled out subject to availability of resources.

These are just some highlights from the Act, which further elaborates on various aspects such as procedures, coverage tariffs, limits, approval processes, and eligibility criteria. The detailed provisions aim to ensure comprehensive healthcare access and financial protection under SHIF.

Section III: Legal Status of the Social Health Insurance Fund

Kenya’s democracy is marked by a robust and dynamic legal culture where citizens, civil society, and even government entities regularly challenge laws and regulations in court. This litigious nature is not a sign of dysfunction but rather a testament to Kenya's constitutional democracy, where judicial oversight plays a crucial role in maintaining checks and balances. Nearly every significant law, from electoral regulations to tax policies and health reforms, undergoes judicial scrutiny, emphasizing the courts' role as a protector of constitutional rights. The Social Health Insurance Act was no exception.

In a constitutional petition filed by Joseph Enock Aura, on 19th July 2024, the High Court declared some provisions of the Social Health Insurance Act (SHIA), the Digital Health Act (DHA), and the Primary Health Care Act (PHCA) unconstitutional primarily because of infringement to the right to emergency treatment, but suspended the effect of its judgment for 120 days to allow for amendments to the unconstitutional provisions and public participation. A three-judge bench found that Sections 26 (5) and 27 (4) of the Act were unconstitutional to the extent that they violated the right not to be denied emergency medical treatment as guaranteed by the Constitution. Further, the Court found that the Acts were enacted without sufficient public participation. In the judgment, the court directed that Parliament amend the unconstitutional provisions and undertake sensitization, adequate, reasonable, sufficient, and inclusive public participation. Section 26 (5) had made registration and contribution as a precondition for accessing public services from national and county government hospitals while section 27(4) provided that one could only access healthcare when their contributions were up-to-date and active.

The Cabinet Secretary for Health later filed an appeal against the judgment of the High Court and simultaneously sought a stay of the High Court judgment pending the determination of the appeal resulting in the Court of Appeal’s pronouncement on 20th September 2024, which stayed the High Court’s judgment pending the hearing and determination of the substantive appeal.

As it stands, the three Acts remain fully operational even as we await the final verdict on their constitutionality. On 23rd September 2024, the Ministry of Health issued a public notice to all employers, reminding them to register all their employees ahead of the transition date, which was set for 1st October 2024.

Section IV. Implementation of the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) in Kenya

SHIF officially commenced operations on 1st October 2024, as per a government directive. The Ministry of Health is in the final stages of transitioning from NHIF to SHIF, with new operational structures set up under the Social Health Authority (SHA), which will oversee SHIF's management and ensure compliance with the new law. Employers were mandated to register their employees and dependents with SHA, ensuring a smooth handover from NHIF, which had a deadline of 30th September 2024, while unregistered members from NHIF were transferred to the new fund. Key operational guidelines have been issued, with payments made before 9th October 2024 credited to NHIF and those made thereafter allocated to SHIF. Starting with the October 2024 payroll, employers are required to deduct 2.75% from employees’ gross salaries, subject to a minimum of Kshs 300.0 per month, and remit these to the Social Health Authority (SHA).

Ahead of the 1st October 2024 rollout, only about 2.0 mn Kenyans had registered with SHA as of 29th September 2024. According to the Ministry of Health of Kenya, as of 10th October 2024, over 12.7 mn Kenyans have registered under SHA, with 1,442 healthcare providers contracted to deliver services to registered members. This number of registrations includes verified members who were under the defunct NHIF and who have been transitioned to the Social Health Authority as per Legal Notice No. 147 of 2024.

This widespread registration has greatly expanded healthcare coverage, ensuring that a significant portion of the population continues to receive essential medical services under SHIF, making healthcare more affordable for low-income households by adjusting contributions based on income, and subsidies are provided to those who cannot afford the premiums. With over 1,400 contracted healthcare providers, SHIF has expanded the healthcare network, improving access.

Despite the progress, SHIF faces a number of challenges:

- System and operational failures: The rollout of Kenya's Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) has faced significant challenges, particularly with its transition from the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF). One of the primary shortcomings has been technical failures in SHIF's claims processing system, including widespread issues with the biometric system. These glitches have left many patients unable to access healthcare services, as their NHIF cards were deactivated before SHIF's system was fully functional,

- Expensively Procured Technology System: The government procured an integrated healthcare information Technology system from a Safaricom-led consortium at a staggering cost of Kshs 104.0 bn, a number that has been in public discourse as overly priced. Despite the cost, the system is yet to be fully operationalized and has seen hospitals go back to the old NHIF system. With the NHIF system already one of the few aspects of the fund that was functional, this further emphasizes the public’s concern about the wastage of resources,

- Healthcare Provider Pushback: In addition to technical difficulties, there is a lack of clarity surrounding SHIF's contractual arrangements with healthcare providers. Many hospitals have expressed concerns over who will reimburse them for services rendered, as formal agreements between SHIF and facilities are yet to be solidified. This uncertainty has contributed to financial strain on patients, some of whom are being asked to pay out-of-pocket for services that should have been covered by the insurance,

- Capitation Model: While the ministry and stakeholders rush to complete the transition from NHIF to SHIF, the model for capitation for the new fund is yet to be fully operationalized. According to the Rural and Urban Hospitals Association of Kenya, the technical working group has only achieved three out of the ten set tasks, that is setting up, creating a draft proposal, and first meeting. Crucial items such as identification of hospitals, patient redistribution, and fund disbursements are still pending,

- The Means-Testing System: Just like the university model system, this means-testing system introduced through this model has so many deficiencies, with the major one being the complexity and almost impossibility of accurately assessing the financial states of households and individuals in the majority of the informal economy. There is a definite risk of exclusion errors, where vulnerable individuals may be denied access due to misclassification or lack of documentation. This means testing fails to capture real needs, as income alone doesn’t account for factors like family size or chronic illness, and it risks creating regional disparities due to varying costs of living across Kenya,

- Delayed Training: Medical administrators, patients, and required stakeholders have not been taken through one session of training regarding the operations of the new systems. This has paralyzed some operations such as preauthorization and claim submissions for surgical patients. The government says it is still monitoring the new system in order to completely understand it before going out to train in various hospitals,

- Unnecessary Limits to Benefits Covered: SHIF introduced a payroll deduction of 2.75% from employees’ gross salaries, subject to a minimum of Kshs 300.0 per month, which is higher than the previous NHIF contributions and even more so for the higher income earners who were previously offered a flat rate for high-income earners, but now have no maximum limit. Additionally, the Ministry of Health projects collections of up to Kshs 133.0 bn for the first year of SHIF operation, which is more than double the average collections that NHIF has recorded in the last five years. However, the benefits provided, in almost all sections are subject to limits such as specific household amounts or specific hours/days annually. For chronic illnesses, specifically, these kinds of limits are not sensible and serve no purpose for insurance coverage. Limiting inpatient services, for instance, to just 180 days annually for a household, may not work for cancer or even diabetes patients. The chart below shows the comparison between NHIF contributions for the last five years and the projected annual Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) contribution for year one;

- Public Confusion and Resistance: The transition from the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) to SHIF has been poorly communicated, leaving many Kenyans unsure about how the new system works or how it benefits them. Many have expressed frustration with the lack of clarity on coverage and contributions, with some citizens even refusing to migrate to the new system, and,

- Public Trust and Transparency: Past governance issues in NHIF have led to a trust deficit, with concerns over the management of funds and possible corruption. SHIF must demonstrate greater accountability to win back public trust and confidence.

Section V: Case Studies and Recommendations

National and Social Health Insurance Funds are government-sponsored insurance covers aimed at ensuring its citizens get affordable medical coverage irrespective of their socioeconomic status. This enables the citizens to access health care services without having to dig into their pockets to pay medical expenses. In most cases they are mandatory and a portion of the employee’s salary is deducted and remitted to these funds. National Health Insurance Funds have been created in several countries, and often vary in terms of structure and systems of operations. In this topical, we shall focus on the United Kingdom National Health Service and Japan National Health Insurance System. Additionally, we shall discuss key takeouts from the Case Studies;

|

Cytonn Report: Summary of Health Insurance Funds in Various Countries |

|

|

Institution |

Key-Take-outs/Features |

|

Japan National Health Insurance System (NHIS) |

|

|

United Kingdom National Health Service (NHS) |

|

Source: Cytonn Research

In order to ensure the effectiveness of the NHIF, the government in collaboration with the SHIF’s board of management and health services providers can borrow a number of key takeouts from Japan NHIS and UK NHS, and, work together to address some of the challenges faced by the funds. As such, we recommend the undertaking of the following actionable steps:

- Cut Corruption in Healthcare Sector: Corruption is endemic in our society. With collections more than doubling what was being collected in NHIF, there is going to be a concerted effort on corruption through the usual means such as procurement fraud and overpricing of services.

- Transparency, Openness and Accountability: Ensure there is transparency, openness and accountability in the conduct of the affairs of the fund.

- Improve Infrastructure of Public Hospitals: To achieve a Universal Health Care (UHC) system, the government should invest in facilities in public hospitals to ensure they offer quality services, given majority of individuals in rural areas access health services from public hospitals due to difficulty in accessing private hospitals. According to the UK Department of Health and Social Care Annual Report and Accounts 2022-2023, the NHS spent £32.1 bn (Kshs 4.9 tn) to finance the commissioning of new hospitals, renovate the existing health care facilities, and health care equipment among others. UK investment in improving health facilities infrastructure has enabled one of the best health care systems as it is among the top 5 best health systems in the world according to the Common Wealth Secretariat,

- Creation of Strong partnership with both the public and private health services providers: With the bad blood we experienced between NHIF and the local health service providers on the back of delayed remittance of the amounts owed, SHIF should propose to rebuild a cordial relationship with them in order for Kenyan Citizens to access health care services in any health facility. In most instances in the previous system, Kenyans have been forced to pay for health services out of their pockets as some hospitals decline the use of NHIF cards to settle for expenses. In Japan, the good relationship between NHIS and the health service providers has enabled Japan’s residents to have the freedom to access health care services anywhere at any time,

- The Government should have an active role in setting up the Fees charged by the service providers: Given that there have been reports showing that some health service providers participated in altering or falsifying information to increase their payouts from the previous Fund, the government should play an active role in setting the baseline fees for the services offered in health institutions to prevent Kenyans and the fund from being overcharged. In Japan, the government is responsible for preparing the fee schedule entailing all the fees for all the services offered by health institutions and ensuring strict adherence to the schedule, and,

- The government should consider including a subsidy program for SHIF – The elevated prices in food and fuel have reduced Kenyan residents’ disposable income and therefore Kenyans have to dig into their pockets in the event that they have surpassed their limits. Insurance penetration in Kenya continues to remain low compared to other key economies, with insurance penetration at 2.3%, which is below the global average of 7.0%, according to the Swiss RE institute, and is attributable to the fact that insurance uptake is still seen as a luxury and is mostly taken when it is necessary or a regulatory requirement. As such the government should come up with a subsidy program aimed at cushioning Kenyans from the rising medical costs. Case in point; Japan has a subsidy program called the “High Cost Medical Expense Benefit System” aimed at shielding the residents from the burden of medical expenses in the instance they surpass their monthly limits. The system sets the maximum threshold an individual can pay out of pocket depending on the age and income of the residents.

Section VI: Conclusion

The rationale behind the introduction of the Social Healthcare Insurance plan is quite solid and essential for the achievement of the Universal Healthcare goal. However, like with all great ideas, the real challenge lies in the implementation. The transition has so far faced significant challenges that need to be addressed for the new system to succeed. Technical failures in claims processing, healthcare provider pushback, and a lack of clarity in contractual agreements have hindered a smooth rollout. The wastage of resources through, for instance, expensively procured systems further hurt the idea in the eyes of the public. The technological system is one of the areas that NHIF had done really well, with a functional portal and mobile app, that defies the need for a new expensive system. The other issue is in the limits on the covers that make it really discouraging, especially given the increased rates of deduction. By addressing these operational and financial issues, and by fostering strong partnerships with healthcare providers, and considering feedback from the public, SHIF can become a robust, inclusive system that provides quality healthcare for all Kenyans.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication, which is in compliance with Section 2 of the Capital Markets Authority Act Cap 485A, is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.