Following the continued depreciation of the Kenya Shilling against the US Dollar and various sentiments being raised in the recent past with regards to currency manipulation, we decided to do a note to demystify the various currency regimes, the mechanisms under which they operate, and how countries use them to ensure currency stability. We shall also focus on the various techniques used to estimate the value of a currency and the factors that have been driving the downward performance of the Kenya shilling.

In our focus on Currency and Interest Rates, where we looked at the factors that were expected to affect the performance of the Kenyan shilling against the US Dollar. We expected the currency and the interest rates to remain under pressure with the currency depreciation to continue. This mainly because of the predicted reduction in export inflows as some of Kenya’s key trading partners had instituted lockdown measures, as well as, a decline in diaspora remittances;

In this focus we shall cover the following:

- A brief history of currency regimes and the various types used by governments globally,

- How to estimate the value of a currency,

- Kenyan foreign exchange markets and recent events,

- Conclusion and Our View Going Forward

Section I: A Brief History of Currency Regimes

An exchange rate can be widely defined as the value of one currency for the purpose of conversion to another. An example, how many Kenyan shillings you would need to acquire one US Dollar. However, just like in the exchange of goods and services, we must take into account what determines that price. As such, the monetary authority of a country or currency union manages the currency in relation to other currencies and the foreign exchange market through exchange rate regimes which are the frameworks under which the price is determined.

Initially, most countries used the gold standard whose value was directly linked to gold and the money supply was tied to their trade balance; but in the 1930s, most countries abandoned it for the Bretton Woods model due to decline in global trading activities. Under this model, the value of the US dollar was pegged on Gold and all the other currencies were pegged on the value of the US dollar.

An ideal currency regime would have three characteristics. First, all the currencies would be freely exchangeable for any purpose and any amount thus ensuring the free flow of capital. Second, the exchange rate between any two currencies would be fixed to eliminate currency-related uncertainties, especially for goods and services. Third, each country would be free to pursue independent monetary policy objectives.

Types of Currency Regimes across the World:

There are three broad exchange regimes used by various governments across the world, these three regimes as explained in depth in our understanding currency regimes note. This include:

- Fixed Exchange Rate Regime -The monetary authority, or the Central Bank of a given country, tries to maintain a currency value that is constant against another country’s currency or a basket of other countries’ currencies or a specific commodity e.g. gold. Examples of countries using a fixed regimes include Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar. The purpose of a fixed exchange rate system is to keep a currency's value within a narrow range,

- Floating Exchange Rate Regime - This is a regime where the currency value of a given country is allowed to vary according to the foreign exchange market. An example of this is Kenya where we have a floating regime. The currency fluctuates in relation to what is happening in the market and therefore the rate is determined by the forces of demand and supply. However, there might be periods of intervention though they are aimed at preventing undue fluctuations rather than setting the rate

- Pegged exchange rate regime - This is an exchange rate regime where the currency is pegged to a band or value, which is fixed or periodically adjusted or also pegged on other countries currency. The band is determined by international bilateral agreements or by a monetary authority and are adjusted periodically in response to economic conditions and indicators. An example of countries using this regime is; Ethiopia and China – whose currencies are fixed to a basket weighted towards the US dollar.

It is difficult to maintain the three conditions for an ideal currency regime, therefore each country chooses the regime that suits their policy objectives. Previously, there have been instances where a country has switched from one regime to another. Here is a look at examples of countries that have shifted their exchange regimes over the years;

- Botswana – In 1976, Botswana broke ranks with the rand zone and established its currency - the Pula and an adjustable peg regime, initially to the dollar and later to a basket composed of the rand at 70% and the IMF’s Special drawing rights (SDR) SDR at 30%. The Pula remained pegged to the US dollar until June 1980 when a significant appreciation of the rand against the US dollar, due to the increase in gold prices necessitated South Africa, a key component of the basket, to shift to a managed float. In particular, the depreciation of the Pula against the rand caused inflation in Botswana to accelerate to around 16.4%. Subsequently, Botswana shifted to a fixed peg regime, which was considered appropriate for their relatively small undiversified economy that was unlikely to sustain a floating currency. In 2005, Botswana introduced the crawling band regime intending to enable an automatic nominal adjustment of the exchange rate with a view of maintaining its stability and avoiding the need for sizeable discrete adjustments as it had been the case in the past,

- Nigeria - Before 1985, Nigeria operated a fixed exchange rate regime. The Government switched to a floating regime, following the fall in oil prices and the push by the World Bank for a Structural adjustment program that would devalue the currency and restore economic growth. Over the years the Nigerian government has switched in between various exchange regimes as they try to find a regime that would facilitate the achievement of both external and internal balances on the economy. In 1986 the government switched to a managed float system, with introduction of the Second-tier Foreign Exchange Market (SFEM) as a market-driven mechanism for foreign exchange allocation. The most of the 90’s the government used the Autonomous Foreign Exchange Market (AFEM) and introduced the Dutch auction system in 2002 – which reduced the dependence of authorized dealers on the Central Bank of Nigeria for foreign exchange and help achieve a convergence in exchange rates. However, following the 2008 financial crisis the Naira gradually depreciated against the dollar to N153.90/USD in 2011. When the initial devaluation in 2014 failed to counter the depreciation in the value of the naira, the Central Bank in February 2015 sought to limit the amount of foreign currencies that could be procured directly from them, by closing both its retail and wholesale auction windows. Despite these interventions, the value of the Nigerian naira continued to depreciate as a lot of demand could not be met by the market. Therefore, in June 2016, the managed float exchange rate system titled “Flexible Exchange Rate Inter-bank Market” was reintroduced. The system brought about a fragmented exchange rate system which offered multiple rates at different windows, the system has however led to speculative demand, profit taking pressures and thriving of a recognized black market dollar exchange rate.

Section II: How to Determine the Value of a Currency

One would then ask how you estimate the exchange rate between 2 countries and the value of the country’s currency. The most widely used methods are:

- The purchasing power parity (PPP) model - which states that the exchange rate between the domestic currency and any foreign currency will adjust to reflect differences in the inflation rates between them. The PPP looks at the prices of commodities in different countries and is the widely used method of forecasting exchange rates. According to PPP, the price of a loaf of bread in Kenya should the same price in any other country even after taking into account the prevailing exchange rate and excluding the accompanying transaction costs. However, PPP is faced with several challenges since countries typically have different baskets of goods and services produced and consumed. Hence, most of these goods and services are not traded internationally due to trade barriers and transaction costs (e.g., shipping costs and import taxes). Consequently, nominal exchange rates persistently deviate from PPP as relative purchasing power among countries displays a weak propensity to long-term equalization.

- Real effective exchange rate (REER): This is a measure of the value of a currency determined as the weighted average of a country’s currency that is relative to a basket of other currencies. The weights are a function of the relative trade balance of a given country’s currency against each country in that basket. An increase in the REER implies that exports have become more expensive with imports becoming cheaper; subsequently, an increase indicates a loss in trade competitiveness.A country’s REER is found by taking the bilateral exchange rates between itself and all of its trading partners, then weighting by the trade allocation associated with each country and multiplying by 100 to form an index.

- Behavioral equilibrium exchange rate (BEER): The model was developed by Clark and MacDonald (1999) and estimates the fair value of currencies according to short, medium and long-run determinants. The model attempts to measure possible exchange rate misalignment between any given two currencies based on monetary policy, terms of trade, chance disturbances, national savings and current economic fundamentals in relation to their sustainable levels. The method is often employed using econometric applications and can often be used to explain cyclical changes in the currency. The choice of variables for the BEER approach is discretionary and is based on beliefs of what impacts an exchange rate and the available data.

- Fundamental Equilibrium Exchange Rate (FEER): The method assumes the fundamental value should be one that is expected to generate a current account of some surplus or deficit that is equal to the country’s underlying capital flow. This makes the assumption that a country is looking to pursue internal balance and not restricting trade and capital flows to keep its balance of payments at a certain level. For example, if a country wants to peg its exchange rate, it either needs to forgo having an independent monetary policy - so as to allow capital inflows and outflows to move as needed or restrict its capital account with the intention to continue the autonomy over its monetary policy.

With countries trying to implement various exchange rates the question of finding the true value of a currency then comes in. Currency manipulation has been one of the most controversial economic issues in the limelight for the past years. Central banks across the world have been accused of managing the value of their currency during their routine interventions to counter monetary shocks. Currency manipulation is the artificial lowering of a country’s currency value that provides it with an unfair advantage of lowering the cost of their exports. The US produces a bi-annual report identifying countries that are classified as manipulators. In 2019, the US accused China of manipulation but later withdrew the claims. Currently, the IMF has developed guidelines on identification and control of currency manipulation. However, it faces challenges in implementation and is still looking at the best way to deal with manipulators.

Factors that affect the performance of the currency

- Economic stability: Factors like the Economic growth, interest rates and inflation rates influence the perception of a countries attractiveness as an investment destination affecting the performance of the of the country,

- Balance of payment position: The currency will always adjust based on the performance of the net inflow position from both trade and also capital inflows. A significant change in either direction would lead to a complete shift in the normal pegging of the currency,

- Forex reserves amounts held: depending on the country’s economic performance they are required to maintain certain levels of reserves significant deviation of those leads to changes in the currency performance,

- Political stability: In cases where there has been a lot of political turmoil the currencies are significantly affected meaning that people would be fleeing from those countries, and,

- Monetary policies: The aim of monetary policies is to maintain price stability and any changes in that could lead to significant volatilities to the currency.

Section III: Kenya's Foreign Exchange Market and Recent Events

Since independence, the Kenyan exchange rate has undergone various regime shifts, which have mainly been attributed to economic events. From independence to 1974, the rate was pegged to the dollar, which later shifted to a crawling peg after a series of devaluations, then it became fully liberalized in 1993. The current exchange rate regime is free-floating in nature and is determined by the market forces of demand and supply. However, the Central Bank of Kenya frequently participates in the foreign exchange market when; it needs to curtail volatility originating from external shocks, build stocks of foreign reserves, effect government payments and regulate liquidity in the market.

During a country review report released in 2018, the IMF suggested that the Kenyan exchange rate was overvalued by 17.5%. This was attributed partly to CBK engaging in periodic foreign exchange interventions, reflecting the limited movement of the shilling relative to the US dollar. The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) governor, Dr. Patrick Njoroge, however, refuted the claims in a media briefing, coming out to clarify that the Central Bank does interventions in the market which can be seen as manipulations but they were actions that fall within the purview of the bank. Recently, there were also suggestions that the US had cautioned the Kenyan government against currency manipulation, a fact that the Governor clarified that it is a clause the US government includes in all its trade negotiations.

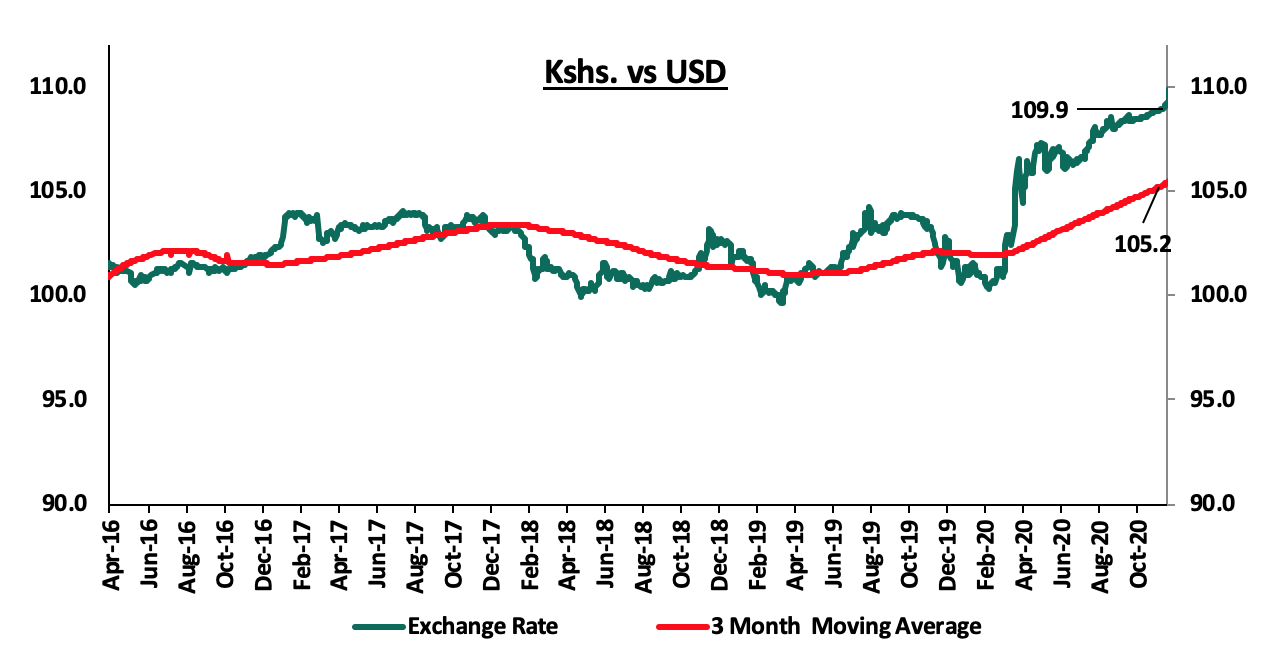

At the start of 2020 the Kenyan Shilling was exchanging at Kshs 101.4 against the US Dollar but due to the effects of COVID-19 weighing down on the economy the shilling has since depreciated by 8.4% to close at Kshs 109.9 at 27th November 2020 as highlighted in the chart below:

The recent performance of the shilling has been affected by:

- The Covid-19 pandemic weighing down on the economy by creating continued uncertainty that increases the demand for dollars globally, as people prefer holding dollars and other hard currencies. Thus pilling pressure on the Kenyan shilling and even after CBK’s intervention the shilling has continued to depreciate,

- The US Dollar appreciating by 6.8% in Q1’2020 against other currencies in the world. Though the gains have since been reversed the Dollar remains strong especially against currencies from emerging economies, Kenya included,

- Dwindling Forex reserves, after a decline in inflows from supporting sectors like tourism, currently stand at USD 7.9 bn (equivalent to 4.9-months of import cover). This has been mitigated by the resilient diaspora remittance inflows – with a 17.3% y/y increase to USD 263.1 mn in October 2020, from USD 224.3 mn recorded over the same period in 2019. This has cautioned the shilling against further depreciation.

Our in- house view is that the shilling will remain under pressure and we expect it to trade against the dollar at a range of Kshs 107.5- 109.5 in the short term. We expect the shilling to be cushioned from further shocks by:

- The Government agreed a USD 2.3 bn credit drawdown facility with the IMF, Kenya targeting an initial disbursement of about USD 725.0 mn in this fiscal year. The facility will be a welcome relief to the currency as it will aid in boosting the forex reserves and help improve market sentiments. This was after the IMF completed its virtual mission to Kenya identifying that the country has suffered unprecedented shock from pandemic and held discussions on discussed with the authorities on a program to support the next phase of their COVID-19 response.

- The fast-tracking of the Covid-19 vaccine that will help in containment of the pandemic and opening of economies. This will be most beneficial to struggling sectors like tourism and horticultural exports who are huge forex contributors, and,

- Monetary policy support from CBK by maintaining the policy rate at the current 7.0%, a further reduction would lead to a further depreciation of the shilling.

Section IV: Conclusion and Recommendations going forward

Determining the “true value” of a currency can be challenging given the various models used and the fact that countries have diverse economic dynamics and challenges.

The continued depreciation of the Kenyan shilling is expected to have the following effects to the economy;

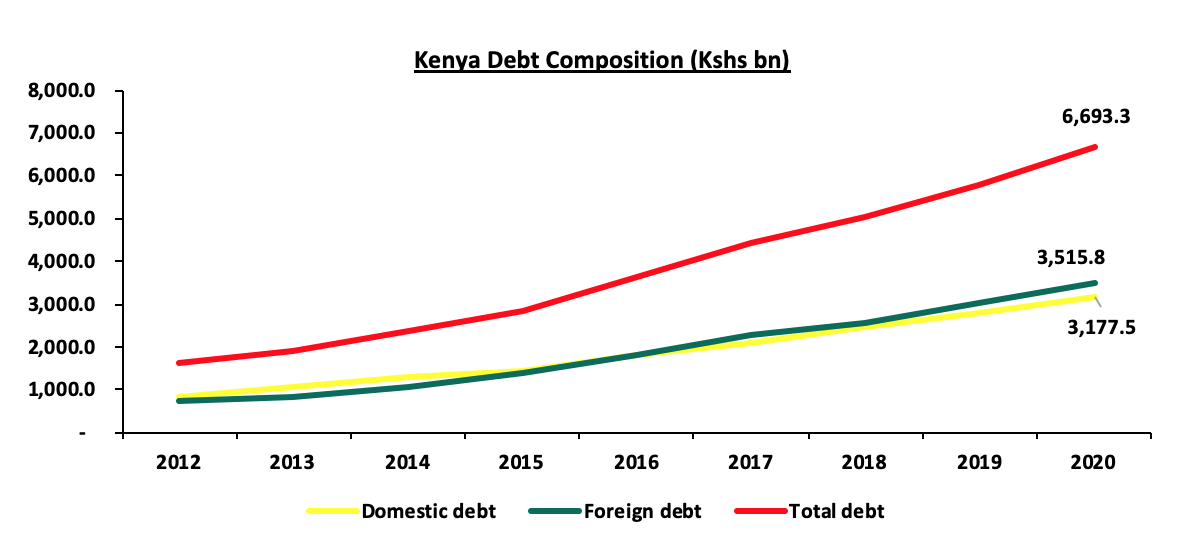

- Foreign debt Repayment: The current debt mix comprises of Kshs 3.2 tn of domestic debt against Kshs 3.5 tn of foreign debt. The government in its Q1 budget outturn for Fiscal year 2020/21 has indicated that it expects to spend Kshs 154.6 bn in foreign debt interest payments. Further depreciation of the shilling will increase the interest debt payments. For instance a 1% depreciation in currency value would increase the interest payments by Kshs 15.5 bn.

The figure below shows Kenya’s debt composition as of June 2020 with 55.2% of the total debt being foreign borrowing:

However, the government has also indicated on a possibility of joining the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), aimed at allowing low-income countries to concentrate resources on fighting the pandemic. The ministry has also indicated that joining the initiative could save the country around Kshs 70-75 bn in interest payments.

2. Making imports more expensive: Kenya is a Net importer meaning that Kenya Imports more than it exports goods and services, therefore further depreciation will make the imports more expensive and with the current account deficit improving in will see the importers spend more to bring commodities into the country. The adjustment in Kenya’s price levels relative to those of its trading partners is however expected to be positive in helping the economy adjust to the COVID-19 shock and stage a recovery, by increasing the international competitiveness of goods and services produced in Kenya.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the writers where particulars are not warranted. This publication, which is in compliance with Section 2 of the Capital Markets Authority Act Cap 485A, is meant for general information only and is not a warranty, representation, advice or solicitation of any nature. Readers are advised in all circumstances to seek the advice of a registered investment advisor.